The Shape of a Turing Machine

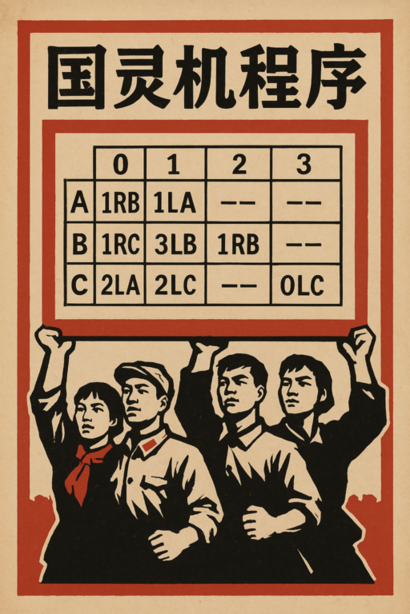

Recently I found an interesting Turing machine program. When started on a blank tape, it runs for more than 101565 steps before halting. Here it is1:

What’s special is that this is, as far as anyone knows, the longest that a Turing machine program of eight instructions can run.

Now, this might sound familiar to you if you’ve heard of the Busy Beaver game. The goal of that game is to find the longest running Turing machine of a given length. However, program length has traditionally been measured by number of states and colors, rather than total number of instructions. So we say, for example, that a program is 5-state 2-color (5x2), or 2-state 4-color (2x4), etc. We call a program’s particular number of states and colors its shape.

A fully specified N-state K-color halting program has NK - 1 instructions (-1 because reaching an undefined instruction is what it means to halt), and so NxK programs have the same number of instructions as KxN. It is therefore natural to wonder whether there might be some relationship between the two classes, or whether there might be a way to convert an NxK program to KxN form, or whether the two categories ought to be somehow grouped together.

There is a point of view that says this approach is nonsensical because it ignores the real semantic difference between states and colors. In fact states and colors correspond to fundamental control flow constructs, namely jumping and branching. An NxK program has N jump targets, each of which executes a K-way branch.

For example, consider the 4x2 Busy Beaver champion program, discovered by Allen Brady in 1964, and the 2x4 champion, discovered by Shawn and Terry Ligocki in 2005:

+-----+-----+ +-----+-----+-----+-----+

4x2 | 0 | 1 | 2x4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

+---+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| A | 1RB | 1LB | | A | 1RB | 2LA | 1RA | 1RA |

+---+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| B | 1LA | 0LC | | B | 1LB | 1LA | 3RB | --- |

+---+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| C | --- | 1LD |

+---+-----+-----+

| D | 1RD | 0RA |

+---+-----+-----+The difference in shape between these programs is visually manifest, and it becomes especially pronounced when they are transliterated into C:

main() { /* 4x2 */

A:

switch (READ) {

case 0: { PRINT(1); RIGHT; goto B; }

case 1: { PRINT(1); LEFT; goto B; }

}

B:

switch (READ) {

case 0: { PRINT(1); LEFT; goto A; }

case 1: { PRINT(0); LEFT; goto C; }

}

C:

switch (READ) {

case 0: { return; }

case 1: { PRINT(1); LEFT; goto D; }

}

D:

switch (READ) {

case 0: { PRINT(1); RIGHT; goto D; }

case 1: { PRINT(0); RIGHT; goto A; }

}

}

main() { /* 2x4 */

A:

switch (READ) {

case 0: { PRINT(1); RIGHT; goto B; }

case 1: { PRINT(2); LEFT; goto A; }

case 2: { PRINT(1); RIGHT; goto A; }

case 3: { PRINT(1); RIGHT; goto A; }

}

B:

switch (READ) {

case 0: { PRINT(1); LEFT; goto B; }

case 1: { PRINT(1); LEFT; goto A; }

case 2: { PRINT(3); RIGHT; goto B; }

case 3: { return; }

}

}There is no apriori reason to believe that it should be possible to somehow convert back and forth between jump targets and switches, and so we might say that it is ridiculous to compare NxK programs with KxN. They are apples and oranges.

But wait, not so fast. Actually there is a way to commensurate NxK and KxN programs: simply interpret them both as max(N,K) x max(N,K) programs! To use the examples above, this means interpeting 4x2 and 2x4 programs as woefully underspecified 4x4 programs that happen not to avail themselves of all available states and colors:

+-----+-----+-----+-----+ +-----+-----+-----+-----+

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| A | 1RB | 1LB | --- | --- | | A | 1RB | 2LA | 1RA | 1RA |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| B | 1LA | 0LC | --- | --- | | B | 1LB | 1LA | 3RB | --- |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| C | --- | 1LD | --- | --- | | C | --- | --- | --- | --- |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| D | 1RD | 0RA | --- | --- | | D | --- | --- | --- | --- |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+ +---+-----+-----+-----+-----+Now we have a straightforward apples-to-apples comparison between two 4x4 programs each with seven instructions defined. And the results are stark: the 4x2 champ runs for 106 steps before halting, while the 2x4 champ runs for 3,932,963 steps. Wow! This suggests that, in some sense, colors are more powerful than states.

But is it really so simple? Notice that these traditional shape-based programs appear artificially constrained in this new context. Neither of them use the diagonal, for example, and they both have a boxy look. Are there any 7-instruction programs that run longer? If so, what are their shapes? In general, what about N-instruction programs?

This question is known as Instruction-Limited Busy Beaver, or BBi(n) for short. It was first proposed by pseudonymous Internet denizen MrBrain in July 2025. Brain and Shawn were quickly able to establish some definitive early values:

| n | BBi(n) | Shape | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5 | 2x2 | BB(2,2) |

| 4 | 16 | 3x2 | |

| 5 | 37 | 2x3 | BB(2,3) |

| 6 | 123 | 2x4 | |

| 7 | 3932963 | 2x4 | BB(2,4) |

These early results were somewhat disappointing. The hope was that BBi search would turn up some exotic new program shapes. Instead, it confirmed only what was already believed: that colors are more powerful than states. So much more powerful, it would seem, that states were really just a drag, and that the best strategy was to minimize state use entirely.

So I was very pleased when on 26 July 2025 I found a new BBi(8) champ. Not just because of the thrill of discovery, but also because the program had an unexpected shape: 3x4. States may have some use after all! And thus this entry was added to the results table:

| n | BBi(n) | Shape | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 101565 < | 3x4 | 🎉 |

Discussion Questions

- How many states and colors can an N-instruction program use?

- What is the best method for measuring program length?

- What other evidence is there that colors are more powerful than states? Is there any counter-evidence?

- How does BBi relate to Brady’s algorithm?

- How does program shape relate to the Spaghetti Code Conjecture?

- Recently the true value of BB(5,2) was proved to be 47,176,869. The champion 5x2 program uses 9 instructions. By the lights of BBi, is this a good score?

- Recently mxdys discovered a 6x2 program that runs for pentationally many steps before halting, with a score > 2 ↑↑↑ 5. That program uses 11 instructions. How would you expect this to compare to the true value of BBi(11)?

- There are off-by-one discrepancies between the step counts used in this post and those reported elsewhere. Why?

- Consider the function SHAPE(n) that returns the shape of the BBi(n) champion. Is this function computable? What about its rate of growth?

Open Problems

- Find a better BBi(8) score, or else prove the current champion.

- BB(2,5) > 10 ↑↑ 4. Find a better BBi(9) score, or prove that value.

Footnotes

1 In plain text:

+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| A | 1RB | 1LA | --- | --- |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| B | 1RC | 3LB | 1RB | --- |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+

| C | 2LA | 2LC | --- | 0LC |

+---+-----+-----+-----+-----+