The Spaghetti Code Conjecture

Turing machine programs are sometimes represented as directed graphs. The vertices of the graph are the program’s states and the edges are transitions between states. The program’s print and shift instructions are relegated to being labels for the edges. Here’s an example:

Suppose you have a Turing machine diagram, but you don’t have access to the print and shift instructions. All you have is the graph of the states and their transitions. I don’t know why you don’t have the prints and shifts, but you don’t. Maybe you’re looking at the diagram on an overhead projection and you forgot your glasses. Maybe the diagram was drawn on a whiteboard and somebody walked past and bumped into it and wiped away the instructions. Maybe you had the program on a deck of punch cards but you dropped them and the cards got out of order and now all you can recover are the state transitions. Way to go, you klutz. Try a rubber band next time.

What can you tell about a program given only its state transitions? Certainly it isn’t possible to figure out exactly what the progam does. There’s no way to tell how the machine will interact with the tape. But the program’s logical structure can be discerned. Look at the example above. States 1 and 2 do some kind of initialization for state 3. States 3, 4 and 5 form a loop. States 5, 6 and 7 form another loop. The 3-4-5 can, based on a decision made at state 5, extend to include 5-6-7 loop.

Why was 6 afraid of 7? Becase 7 ate 9. Neden 4 5 korkuyor? Çünkü 5 6 yedi. The one-two-three cat made it across the river, but the un-deux-trois cat sank.

Busy Beaver programs have state transition graphs too. What do you think they would look like in general? What kinds of properties would you expect a Busy Beaver graph to have?

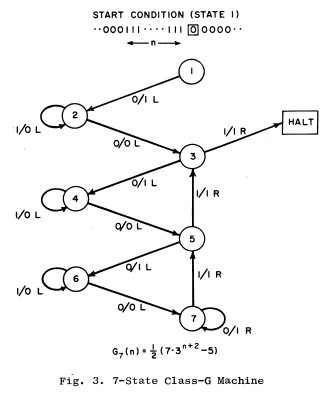

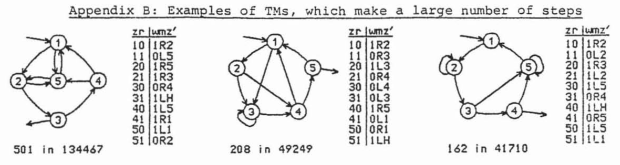

As far as I know, this question was first posed by Joshua Zelinsky in a blog comment. It seems like an obvious question when you hear it, but I haven’t seen any evidence that anyone had ever thought much about Busy Beaver graphs before that. James Harland pointed out that Busy Beaver graphs can’t be disconnected (that is, that there can’t be two nodes between which there is no undirected path), but didn’t go any further. Ludewig, Schult, and Wankmüller compiled an appendix of 100 long-running 5-state programs, each accompanied by a hand-drawn state transition diagram. Look at these nice graphs:

They went to all the trouble of drawing all those diagrams, but their report doesn’t mention the graphs at all. Why not?1

Zelinsky conjectured that all Busy Beavers graphs are strongly connected (that is, that for any two nodes, there is a directed route from one to the other). Call this the strongly connected graph conjecture. Scott Aaronson made a broader and vaguer proposal:

A related intuition, though harder to formalize, is that Busy Beavers shouldn’t be “cleanly factorizable” into main routines and subroutines – but rather, that the way to maximize runtime should be via “spaghetti code,” or a single n-state amorphous mass.

This is the Spaghetti Code Conjecture. On top of spaghetti, all covered with cheese, is the longest-running program of some fixed length. Like Aaronson says, it isn’t a formal statement. It’s a stand-in for a set of formal statements. It implies the strongly connected graph conjecture, for instance, and other statements too. Which statements? That’s a research program. Or maybe it’s a research programme.

I’ll say more about the Spaghetti Code Conjecture, but before that I want to look at an application. And before that I want to say something about the nature of “spaghetti code”.

It’s sometimes defined as code that uses goto statements. But that isn’t right. Donald Knuth uses goto in his programs, and he doesn’t write spaghetti code. “Spaghetti” is a logical property, not a syntactical one. It means that the code’s control flow is convoluted or unduly complex. It’s not enough for the control flow to be just complex, it has to be unduly complex. If the code is modeling something that is complex using control flow that is simple, it’s probably wrong. Spaghetti code has a control flow that is more complex than it needs to be.

Believe it or not, a lot of code that is written by professional programmers is spaghetti. Shocking, I know, but true. Spaghetti code is often not created intentionally. It can result from carelessness, or even a lack of taste. Here are two ways of setting a variable to some conditionally chosen value:

## ternary expression ##################

var = this() if test() else that()

## if / else ###########################

if test():

var = this()

else:

var = that()The ternary expression is obviously the better choice here. It has a simpler control flow. One assign statement, one path. The if-else block has two assign statements, each executed on a separate path. It’s spaghetti-er than the ternary. It’s also much more common. Is that a coincidence? A general lack of taste would explain the correlation. It could explain some other things too.

It really isn’t accurate to describe a Busy Beaver program as “spaghetti”. Spaghetti has a flimsy structure, great for slurping. You wouldn’t want to eat something with the structure of a Busy Beaver program. It would be unpleasant going down and unpleasant coming back up. And make no mistake, it would come back up.

Anyway, on to the application of the Spaghetti Code Conjecture. A program can be converted to a state transition graph by ignoring its print and shift instructions and considering only the states. Now go the other direction. Given an n-state k-color state transition graph, how many concrete programs correspond to it? In other words, how many ways are there to decorate the graph with print and shift instructions? There are nk transitions. Ignoring normalization, each transition gets a left or right shift and one of the k colors. That makes 2k decorations per transition, and so 2nk2 programs per graph. Is that right? I hope so. That means 40 programs per graph in the ❺② case, and 54 programs per graph in the ❸③ case.

This fact can be applied to Busy Beaver searching. The naive search method generates all n-state k-color programs and then searches them. But the total number of programs gets out of hand fast, growing on the order of O((nk)nk). A better way to do it is to generate the possible graphs first and then decorate them with instructions. The Spaghetti Code Conjecture can then be used at graph-generation time to discard graphs that seem unsuitable. (How many program graphs are strongly connected? I have no idea. That’s a sophisticated calculation, and I don’t know what I’m doing.) Discarding a few graphs means discarding a whole swath of programs. It can’t be overemphasized how many programs there are. Discarding them is like bailing water out of a ship. There is no choice but to get rid of a lot of them, and as quickly as possible.

This isn’t just idle speculation. I used the graph decoration technique along with Zelinsky’s strongly connected graph conjecture to find the reigning ❹② Beeping Busy Beaver champion. The conjecture has predictive power! So as far as I’m concerned, its value has already been proved.

Wait, did somebody say “proved”? Like, the conjecture has been formally proved? No, of course not. I doubt it can be proved at all. It might even be provably unprovable. But it could nevertheless be true. Busy Beaver searchers are interested in establishing lower bounds, not upper bounds. If a conjecture leads to better lower bounds, that’s good enough.

How much wood would a woodchuck chuck? Would a beaver eat spaghetti? Raccoons sure do love rummaging through my trash, I can tell you that.

Here’s an argument that the strongly connected graph conjecture is true. It’s not a real proof, just a suggestive argument. Argument by induction on the number states, with fixed k colors. 0- or 1-state programs are trivial and/or degenerate, so start with the base case of 2 states, A and B. Busy Beaver programs run on the blank tape, so the program starts in transition A0. If it stays in state A, then it will remain on transition A0 forever, and is therefore junk. So A0 must transition to B. Does B have any connections to A? If it doesn’t, then the program will spend the rest of its execution time in its k B transitions, and won’t be able to use the full 2k transitions available. But surely such a program can’t be the ❷ⓚ Busy Beaver. Kinda QED on the base case. Next, the induction step. The n-state Busy Beaver is strongly connected. What about the n+1-state Busy Beaver? Suppose it isn’t strongly connected. For simplicity, suppose also that n+1 is the least number of states for a Busy Beaver program whose state graph is not strongly connected. Every Busy Beaver program through n states is strongly connected spaghetti, but then some kind of structure gets introduced at n+1? Why? What kind of structure? Why n+1, and not earlier or later? It seems unlikely. The inductive step is kinda done, and that takes care of the loosey-goosey informal argument.

So we think that Busy Beaver program graphs should be strongly connected. What other properties should they have? I’m now going to enter into the territory of rank speculation and propose a few properties that seem like they should hold. Some caveats:

- Busy Beaver programs need to halt, and that means they need to include a halt state (exactly one, in fact). Inclusion of the halt state makes for a lot of exceptions to otherwise general statements. I don’t feel like making that explicit, so just assume that the exception is there. This doesn’t apply to Beeping Busy Beaver programs, because they don’t indicate program termination in such a clumsy fashion. In general, halt-free programs will have a more pleasing graph structure than programs with a halt instruction.

- These conjectures are meant to apply n-state programs where n is “sufficiently large”. This is great for the conjecturer, as it effectively means the conjecture cannot be falsified. Any counterexample can be dismissed as being “not sufficiently large”. The “no true Scotsman” defense is built right in.

With that, here are some ideas about how an n-state k-color Busy Beaver program graph should look.

- Every node should have as many distinct exit points as possible. Structured programming is all about constraining control flow to operate in an orderly fashion. Spaghetti code is the opposite, so control flow should be constrained to operate in as wild a fashion as possible.

- Every node should have as many distinct entry points as possible. See previous point.

- No reflexive nodes. That is, no states should transition to themselves. One way of interpreting the Spaghetti Code Conjecture is that the state graph should not betray any meaningful information about program control flow. But a state that transitions to itself is obviously some kind of loop. Note that this conjecture is false for some known Busy Beaver champions. I guess they aren’t “sufficiently large”.

- Connections should be distributed as evenly as possible among nodes. If connections are not distributed evenly, then some states will have more entry / exit points than others. But that discrepancy could be used to do some static analysis and figure out information about the program, and that shouldn’t be possible.

- The graph should be k-connected. That is, it should be possible to remove up to k-1 nodes from the state graph without disrupting strong-connectedness. This is a good property for a computer network to have, and it’s also a good property for a program of maximal runtime.

Discussion Questions

- What are some other “spaghetti code” properties?

- BB(4, 2) = 107, but BB(2, 4) = 3932964. What does this have to do with the Spaghetti Code Conjecture?

- Do any of the proposed spaghetti code properties imply each other?

- The conjectured graph properties here yield smooth, even graphs, effacing the identites of the individual nodes. Does this seem likely?

- The natural state of code in the wild is to devolve into spaghetti. Who is to blame?

- Busy Beaver programs seem to be too clever to be written. But the graph analysis approach attempts to do some of the writing. Can it succeed? How?

- Are the graphs of Ludewig et al really hand-drawn? Why or why not?

- What did the beaver say when it swam into a wall?

- Why isn’t it widely understood that ternary expressions are better than if-else blocks for simple variable setting?

Footnotes

1 Unrelated to graphs, Ludewig says:

What is the temptation of the Busy Beaver Problem? The mathematicians have taught us that the general Busy Beaver function is non computable. Different from simple mathematical truths, this result pleases our brain, but not our heart (at least not mine). And though we know we cannot win the war against the mathematical law, we would like to win a battle, i.e. to find at least one particular Busy Beaver.