Halt, Quasihalt, Recur

The goal of the Busy Beaver contest is to find n-state k-color Turing machine programs that run for as long as possible before halting. It’s basically an optimization problem: what is the longest finite computation that can squeezed out of a program of a certain length? Or from the flip-side: how much description can be packed into a program of a certain length?

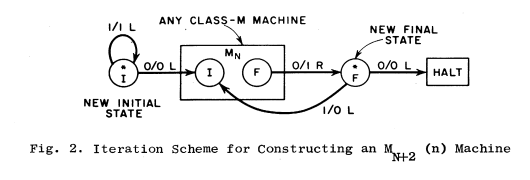

In the early days of the Busy Beaver game, people tried to win with programs they had written themselves, by hand. In 1964 Milton Green devised a method for iteratively constructing longer Turing machine programs from shorter ones. Here’s a diagram with no context:

The details don’t matter. The Green method is computable and the Busy Beaver sequence is not, so it’s clear that the programs thereby produced cannot be optimal, except perhaps among short programs. But it was soon realized that Busy Beaver “champion” programs are too clever to be written, and that therefore the best way to find long-running programs is to search for them. Although they deal with programs, Busy Beaver searchers are more like gold prospectors than they are like programmers.

Still, imagine for a moment that you are a Turing machine programmer and that you’re trying to win the Busy Beaver contest with a handmade program. You have n states and k colors to work with, and so nk print/shift/transition instructions to specify. Where do you start?

The zeroth step, as any good programmer knows, is to review the requirements. In this case, the only constraint on eligibility for a contest entrant program is that it halt. Your program therefore must contain at least one halt transition,1 because a Turing machine only halts when explicitly instructed.2 But this means that you don’t really have nk instructions at your disposal; you only have nk - 1.

This is an annoyance. Other instructions can be looped over and executed many times each, but the halt instruction can executed only once. It doesn’t carry its weight and it bloats the program. Wouldn’t it be nice if you didn’t have to worry about halting? Wouldn’t it be nice to work with a full set of nk instructions? Why does a program need to halt anyway?

From the perspective of a Busy Beaver programmer, the purpose of halting is to signal the end of the computation. The goal is to come up with the longest possible finite computation given a fixed amount of program length, and some specific endpoint for the computation is required, and halting is that endpoint. What other kinds of termination conditions could be used, and what kinds of computations would they yield?

Here’s one way to generalize halting. When a Turing machine halts, all of its states become unreachable. Instead of arranging for all states to become unreachable, a programmer could arrange for some of the machine’s states to become unreachable. The machine wouldn’t actually halt, but it would enter into some kind of degenerate condition, and this would signal the end of the computation. Such a machine is said to have quasihalted, and the use of quasihalting as a termination condition leads to the Beeping Busy Beaver sequence.

Let’s look at some 3-state 2-color (❸②) examples.

The ❸② halting champion program is 1RB 1RH 1LB 0RC 1LC 1LA,3 and it halts after 21 steps. Here is its tape evolution, the longest computation that can be executed by a ❸② program if halting is used as the termination condition:

0 A __________[_]_________

1 B __________#[_]________

2 B __________[#]#________

3 C ___________[#]________

4 A __________[_]#________

5 B __________#[#]________

6 C __________#_[_]_______

7 C __________#[_]#_______

8 C __________[#]##_______

9 A _________[_]###_______

10 B _________#[#]##_______

11 C _________#_[#]#_______

12 A _________#[_]##_______

13 B _________##[#]#_______

14 C _________##_[#]_______

15 A _________##[_]#_______

16 B _________###[#]_______

17 C _________###_[_]______

18 C _________###[_]#______

19 C _________##[#]##______

20 A _________#[#]###______

21 H _________##[#]##______The ❸② quasihalting champion program is 1RB 0LB 1LA 0RC 1LC 1LA, and it quasihalts after 55 steps. Here is its tape evolution over 60 steps:

0 A __________[_]_________

1 B __________#[_]________

2 A __________[#]#________

3 B _________[_]_#________

4 A ________[_]#_#________

5 B ________#[#]_#________

6 C ________#_[_]#________

7 C ________#[_]##________

8 C ________[#]###________

9 A _______[_]####________

10 B _______#[#]###________

11 C _______#_[#]##________

12 A _______#[_]###________

13 B _______##[#]##________

14 C _______##_[#]#________

15 A _______##[_]##________

16 B _______###[#]#________

17 C _______###_[#]________

18 A _______###[_]#________

19 B _______####[#]________

20 C _______####_[_]_______

21 C _______####[_]#_______

22 C _______###[#]##_______

23 A _______##[#]###_______

24 B _______#[#]_###_______

25 C _______#_[_]###_______

26 C _______#[_]####_______

27 C _______[#]#####_______

28 A ______[_]######_______

29 B ______#[#]#####_______

30 C ______#_[#]####_______

31 A ______#[_]#####_______

32 B ______##[#]####_______

33 C ______##_[#]###_______

34 A ______##[_]####_______

35 B ______###[#]###_______

36 C ______###_[#]##_______

37 A ______###[_]###_______

38 B ______####[#]##_______

39 C ______####_[#]#_______

40 A ______####[_]##_______

41 B ______#####[#]#_______

42 C ______#####_[#]_______

43 A ______#####[_]#_______

44 B ______######[#]_______

45 C ______######_[_]______

46 C ______######[_]#______

47 C ______#####[#]##______

48 A ______####[#]###______

49 B ______###[#]_###______

50 C ______###_[_]###______

51 C ______###[_]####______

52 C ______##[#]#####______

53 A ______#[#]######______

54 B ______[#]_######______

55 C _______[_]######______ <-- States A and B become unreachable

56 C ______[_]#######______

57 C _____[_]########______

58 C ____[_]#########______

59 C ___[_]##########______

60 C __[_]###########______At step 55, the machine is in state C and scanning a blank at the left edge of the tape. The program gives the instruction C1 -> 1LC, so it will remain in C forever and so the machine has quasihalted.

That program is halt-free and so will obviously never halt. Nevertheless, something happens in those first 55 steps that is different from what comes after. That “something” can be regarded as a finite computation embedded as a markedly distinct initial segment in an otherwise infinite computation.

The use of quasihalting as a termination condition clearly increases the expressivity of the Turing machine language, since longer finite computations can be captured by the same descriptive resources. For the Turing machine programmer, this is great. More expressivity means shorter programs, and shorter programs are preferable to longer ones.

But now forget about being a Turing machine programmer and imagine yourself to be the implementor of a Turing machine simulator. Rather than making Turing machine programs, you make the thing that executes such programs. Your users are programmers, and they are increasingly vociferous in their demands that you implement quasihalting as a termination condition. That is, they want the simulator to stop running when their programs quasihalt.

In a schematic sense, this should be an easy feature to add. Here is the basic simulator loop logic:

while (1) {

if (IS_HALTED) {

break;

}

PRINT;

SHIFT;

TRANSITION;

}Here is the same loop with an added quasihalting check:

while (1) {

if (IS_HALTED || IS_QUASIHALTED) { // <-- added quasihalting check

break;

}

PRINT;

SHIFT;

TRANSITION;

}It looks like it should be easy to do this, but there’s a catch. Recall that the halt-ing problem asks whether an arbitrary machine will eventually halt. Of course, that problem is undecidable. Now consider the halt-ed problem, which asks whether a machine is currently halted. This question is trivial to answer; it’s implementation-specific, but it amounts to checking the machine’s current state and seeing if it’s the halt state. Every Turing machine simulator in effect solves the halted problem on every machine cycle.

Corresponding to these are the quasihalting problem and the quasihalted problem. The quasihalting problem is super-undecidable, and cannot be solved even with an oracle for the halting problem. The bad news is that quasihalted problem is equivalent to the halting problem; to ask a simulator to implement quasihalting detection in general is in effect to ask it to solve the halting problem on every machine cycle! So if you are a simulator-implementor and your programmer-users are demanding this feature, you definitely will not be able to deliver it. It’s logically impossible.

Suppose that you’ve explained this situation to the users of your simulator, and they still demand more expressivity – that is, they want to extend the longest finite computation that can be expressed within a program of some length. The crux of the issue seems to be the termination predicate. Quasihaltedness is wildly extravagant because of its uncomputability, but logically any computable predicate could be used.

As it happens, the Lin-Rado proof that BB(3) = 21 furnishes a nice computable predicate, which I call Lin-Rado recurrence (or just “recurrence” for short). I won’t describe it in detail here; see “The Lin-Rado Busy Beaver Proof” for a full description. A machine that has entered into recurrence will repeat a certain simple pattern over a fixed (possibly moving) span of tape forever. The pattern will have a certain period, which is the number of steps that it takes to execute the pattern before repeating.

Recurrence patterns are generally “stupid”, so we can plausibly regard entry into recurrence as a termination condition. This termination condition gives rise to yet another Busy Beaver-like sequence: BBLR(n, k) is the longest an n-state k-color Turing machine can run before entering into recurrence.

The BBLR(3, 2) champion program is 1RB 1LB 0RC 0LA 1LC 0LA. It runs for 101 steps before it enters into a recurrence of 24 steps. Here is its tape evolution over 150 steps:

0 A _______________[_]______________

1 B _______________#[_]_____________

2 C _______________#_[_]____________

3 C _______________#[_]#____________

4 C _______________[#]##____________

5 A ______________[_]_##____________

6 B ______________#[_]##____________

7 C ______________#_[#]#____________

8 A ______________#[_]_#____________

9 B ______________##[_]#____________

10 C ______________##_[#]____________

11 A ______________##[_]_____________

12 B ______________###[_]____________

13 C ______________###_[_]___________

14 C ______________###[_]#___________

15 C ______________##[#]##___________

16 A ______________#[#]_##___________

17 B ______________[#]#_##___________

18 A _____________[_]_#_##___________

19 B _____________#[_]#_##___________

20 C _____________#_[#]_##___________

21 A _____________#[_]__##___________

22 B _____________##[_]_##___________

23 C _____________##_[_]##___________

24 C _____________##[_]###___________

25 C _____________#[#]####___________

26 A _____________[#]_####___________

27 B ____________[_]#_####___________

28 C _____________[#]_####___________

29 A ____________[_]__####___________

30 B ____________#[_]_####___________

31 C ____________#_[_]####___________

32 C ____________#[_]#####___________

33 C ____________[#]######___________

34 A ___________[_]_######___________

35 B ___________#[_]######___________

36 C ___________#_[#]#####___________

37 A ___________#[_]_#####___________

38 B ___________##[_]#####___________

39 C ___________##_[#]####___________

40 A ___________##[_]_####___________

41 B ___________###[_]####___________

42 C ___________###_[#]###___________

43 A ___________###[_]_###___________

44 B ___________####[_]###___________

45 C ___________####_[#]##___________

46 A ___________####[_]_##___________

47 B ___________#####[_]##___________

48 C ___________#####_[#]#___________

49 A ___________#####[_]_#___________

50 B ___________######[_]#___________

51 C ___________######_[#]___________

52 A ___________######[_]____________

53 B ___________#######[_]___________

54 C ___________#######_[_]__________

55 C ___________#######[_]#__________

56 C ___________######[#]##__________

57 A ___________#####[#]_##__________

58 B ___________####[#]#_##__________

59 A ___________###[#]_#_##__________

60 B ___________##[#]#_#_##__________

61 A ___________#[#]_#_#_##__________

62 B ___________[#]#_#_#_##__________

63 A __________[_]_#_#_#_##__________

64 B __________#[_]#_#_#_##__________

65 C __________#_[#]_#_#_##__________

66 A __________#[_]__#_#_##__________

67 B __________##[_]_#_#_##__________

68 C __________##_[_]#_#_##__________

69 C __________##[_]##_#_##__________

70 C __________#[#]###_#_##__________

71 A __________[#]_###_#_##__________

72 B _________[_]#_###_#_##__________

73 C __________[#]_###_#_##__________

74 A _________[_]__###_#_##__________

75 B _________#[_]_###_#_##__________

76 C _________#_[_]###_#_##__________

77 C _________#[_]####_#_##__________

78 C _________[#]#####_#_##__________

79 A ________[_]_#####_#_##__________

80 B ________#[_]#####_#_##__________

81 C ________#_[#]####_#_##__________

82 A ________#[_]_####_#_##__________

83 B ________##[_]####_#_##__________

84 C ________##_[#]###_#_##__________

85 A ________##[_]_###_#_##__________

86 B ________###[_]###_#_##__________

87 C ________###_[#]##_#_##__________

88 A ________###[_]_##_#_##__________

89 B ________####[_]##_#_##__________

90 C ________####_[#]#_#_##__________

91 A ________####[_]_#_#_##__________

92 B ________#####[_]#_#_##__________

93 C ________#####_[#]_#_##__________

94 A ________#####[_]__#_##__________

95 B ________######[_]_#_##__________

96 C ________######_[_]#_##__________

97 C ________######[_]##_##__________

98 C ________#####[#]###_##__________

99 A ________####[#]_###_##__________

100 B ________###[#]#_###_##__________

101 A ________##[#]_#_###_##__________ <-- first recurrence starts

102 B ________#[#]#_#_###_##__________

103 A ________[#]_#_#_###_##__________

104 B _______[_]#_#_#_###_##__________

105 C ________[#]_#_#_###_##__________

106 A _______[_]__#_#_###_##__________

107 B _______#[_]_#_#_###_##__________

108 C _______#_[_]#_#_###_##__________

109 C _______#[_]##_#_###_##__________

110 C _______[#]###_#_###_##__________

111 A ______[_]_###_#_###_##__________

112 B ______#[_]###_#_###_##__________

113 C ______#_[#]##_#_###_##__________

114 A ______#[_]_##_#_###_##__________

115 B ______##[_]##_#_###_##__________

116 C ______##_[#]#_#_###_##__________

117 A ______##[_]_#_#_###_##__________

118 B ______###[_]#_#_###_##__________

119 C ______###_[#]_#_###_##__________

120 A ______###[_]__#_###_##__________

121 B ______####[_]_#_###_##__________

122 C ______####_[_]#_###_##__________

123 C ______####[_]##_###_##__________

124 C ______###[#]###_###_##__________

125 A ______##[#]_###_###_##__________ <-- second recurrence starts

126 B ______#[#]#_###_###_##__________

127 A ______[#]_#_###_###_##__________

128 B _____[_]#_#_###_###_##__________

129 C ______[#]_#_###_###_##__________

130 A _____[_]__#_###_###_##__________

131 B _____#[_]_#_###_###_##__________

132 C _____#_[_]#_###_###_##__________

133 C _____#[_]##_###_###_##__________

134 C _____[#]###_###_###_##__________

135 A ____[_]_###_###_###_##__________

136 B ____#[_]###_###_###_##__________

137 C ____#_[#]##_###_###_##__________

138 A ____#[_]_##_###_###_##__________

139 B ____##[_]##_###_###_##__________

140 C ____##_[#]#_###_###_##__________

141 A ____##[_]_#_###_###_##__________

142 B ____###[_]#_###_###_##__________

143 C ____###_[#]_###_###_##__________

144 A ____###[_]__###_###_##__________

145 B ____####[_]_###_###_##__________

146 C ____####_[_]###_###_##__________

147 C ____####[_]####_###_##__________

148 C ____###[#]#####_###_##__________

149 A ____##[#]_#####_###_##__________ <-- third recurrence starts

150 B ____#[#]#_#####_###_##__________Here are the three sequences corresponding to three termination predicates:

| Sequence | Predicate |

|---|---|

| BB | Haltedness |

| BBB | Quasihaltedness |

| BBLR | LR-recurrence |

Haltedness and LR-recurrence are decidable predicates, while quasihaltedness is not. This implies with certainty that for all sufficiently large values, BBB dominates both BB and BBLR. It also seems likely that BBLR dominates BB for sufficiently large values, since LR-recurrence is a looser termination condition than haltedness.

Here are some concrete early values for these sequences, along with witnessing programs and proof statuses and discoverer. ! indicates known proved values, ? indicates lower bounds that are not known to be optimal, and $ indicates bounds that I believe I have proven with a reasonable degree of certainty (proofs to be published soon!).

| Value | Proved | Program | Discoverer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB(2, 2) | 6 | ! | 1RB 1LB 1LA 1RH |

Rado |

| BBB(2, 2) | 6 | ! | [same as for BB(2, 2)] | |

| BBLR(2, 2) | 9 | $ | 1RB 0LB 1LA 0RB |

Drozd |

| BB(3, 2) | 21 | ! | 1RB 1RH 1LB 0RC 1LC 1LA |

Lin |

| BBB(3, 2) | 55 | $ | 1RB 0LB 1LA 0RC 1LC 1LA |

Aaronson |

| BBLR(3, 2) | 101 | $ | 1RB 1LB 0RC 0LA 1LC 0LA |

Drozd |

| BB(2, 3) | 38 | ! | 1RB 2LB 1RH 2LA 2RB 1LB |

Brady |

| BBB(2, 3) | 59 | $ | 1RB 2LB 1LA 2LB 2RA 0RA |

Drozd |

| BBLR(2, 3) | 165 | ? | 1RB 0LA ... 1LB 2LA 0RB |

Drozd |

| BB(4, 2) | 107 | ! | 1RB 1LB 1LA 0LC 1RH 1LD 1RD 0RA |

Brady |

| BBB(4, 2) | 66349 | ? | 1RB 0LC 1LD 0LA 1RC 1RD 1LA 0LD |

Drozd |

| BBLR(4, 2) | 66349 | ? | [same as for BBB(4, 2)] |

A few trends stick out from this data. First, BBB(2, 2) = BB(2, 2) = 6, so the power of quasihaltedness doesn’t kick in immediately. But BBLR(2, 2) = 9, and indeed BBLR(3, 2) > BBB(3, 2) > BB(3, 2) and BBLR(2, 3) > BBB(2, 3) > BB(2, 3), so recurrence is a more powerful predicate than quasihaltedness for short programs. BBLR(4, 2) = BBB(4, 2) as far as is known, but I don’t have great confidence in this result. BBB will eventually dominate BBLR; why shouldn’t it happen at ❹②? All known quasihalting programs are also LR-recurrent, even though this cannot be true in general. It’s hard to say anything definitive about the ❹② case. As always, more searching is needed.

Open Problems

- Find better values for BBB(4, 2) and BBLR(4, 2), or else prove that the known lower bounds are optimal.

- Devise new termination conditions (either weaker or stronger than the conditions described here) and find champions for their corresponding Busy Beaver-like sequences.

- The Lin-Rado algorithm detects LR-recurrence, but it doesn’t do so until after the machine as finished its first recurrence. Devise an algorithm to detect recurrence at the time that it starts.

- Prove that BBLR dominates BB.

- Find a quasihalting program that is not LR-recurrent.

Footnotes

1 To maximize runtime, you will probably also want at most one halt transition; any more than that would be a waste.

2 This is in contrast to a computing regime like the lambda calculus, where halting is implied by program evaluation. It’s not obvious how to adapt the discussion in this post to such a model.

3 For program notation, see “Turing Machine Notation and Normal Form”.