Are Turing Machines Programmable?

Turing machines can be represented by simple strings:

1RB 1LC 1RC 1RB 1RD 0LE 1LA 1LD 1RH 0LALess compactly but more transparently, they can also be represented as tables:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1RB | 1RC | 1RD | 1LA | 1RH |

| 1 | 1LC | 1RB | 0LE | 1LD | 0LA |

What is the nature of these representations? Are they more like schematics of distinct discrete devices, or are they more like programs for a computer? This amounts to asking: what exactly is a Turing “machine”? Is it imagined to be like one of those old-timey video game consoles that only plays one game, or is it imagined to be like a single video game console with a library of swappable games? And what about a program for executing these representations? Is such a program a simulator, or is it itself a Turing machine?

In a sense, it doesn’t matter. The difference between “program” and “machine” is “just” a matter of perspective1, and in any case it’s “just” a matter of terminology. But I’m a stickler for terminology, and thinking through this question led me to a dramatically faster Turing machine implementation. The rest of this post will walk through this line of thinking.

Simulators

At this point, readers who have not already done so should stop and implement a program for running Turing machines. It should accept Turing machine strings or tables and then do whatever is prescribed. There are a variety of slightly different definitions for Turing machines2, but the details aren’t terribly important.

Whatever language is used, however it’s structured, whatever bells and whistles are included, such a program will ultimately boil down to logic like this:

while state != HALT:

color, shift, state = table[state][tape[position]]

tape[position] = color

position += shiftSuch a program is often described as a “Turing machine simulator”. This makes it sound like the program is simulating a piece of hardware, like an elevator simulator or a pinball machine simulator. In this view, a string or table like the one above is a schematic description, and it describes a single Turing machine that does exactly one thing, namely whatever the schematic says it does. Running a search over some set of strings amounts to simulating a set of distinct machines.

Maybe it’s because I’m not a hardware person, but I find this point of view and its associated terminology strange. When I run a search over a list of Turing machine strings, I imagine a single device successively loading and running a list of programs. In this view, the program with while state != HALT is the Turing machine, and the strings are programs telling that machine what to do. That’s how I think about Turing machines, and the terminology in my programs (like variable and function names) mostly reflects that.

Discrete Devices

So a “Turing machine” is either a device to be simulated or a program to be executed. In either case, our access to the “machine” is mediated through the use of another program. What would it mean to have direct access to a Turing machine?

This “direct access” is desirable for two reasons. The first is speed. Running a program to run another program is obviously slower than just running the program directly. If you want to run through a long list of Turing machine strings in search of something specific (like a Busy Beaver), you cannot afford to run a program that run programs. You need to run the programs straight.3

The second reason is that simulation stifles the spirit of the program. A Turing machine representation describes some computational process. That process can be simulated with the while loop mentioned above, but that is not what the description says to do. What exactly it says to do can be hard to say, since Turing machines are capable of arbitrary control flow. The simulation loop obscures the true nature of the Turing machine being run by imposing on it a structure that can be understood by programmers. If we want to hear what the computational processs has to say, the Turing machine must be free to speak in its own voice.4

So, the Turing machine will be implemented directly. What language should be used? A critical requirement is that the language should be able to support arbitrary control flow, and that narrows the choices down considerably. I imagine it would be possible to express a Turing machine’s compuational process directly in Scheme or some other language with tail call elimination, but for maximum speed I went with C. C features the much-maligned goto operator, and that makes it trivial to transcribe a Turing machine into executable C code.

As an example, consider the Turing machine mentioned above: 1RB 1LC 1RC 1RB 1RD 0LE 1LA 1LD 1RH 0LA. Starting with a blank tape, it runs for 47,176,870 steps before halting. That’s a ponderous computation, and on my feeble laptop it takes my Python simulator 45 seconds to run it.5

Here is how it looks in C, with a few basic metrics captured:

#include <stdio.h>

#define PROG "1RB 1LC 1RC 1RB 1RD 0LE 1LA 1LD 1RH 0LA"

#define TAPE_LEN ((100000 * 2) + 10)

int POS = TAPE_LEN / 2;

int TAPE[TAPE_LEN];

#define ZERO_TAPE for (int i = 0; i < TAPE_LEN; i++) {TAPE[i] = 0;}

#define L POS--

#define R POS++

#define INSTRUCTION(c0, s0, t0, c1, s1, t1) \

if (TAPE[POS]) \

{TAPE[POS] = c1; s1; goto t1;} \

else \

{TAPE[POS] = c0; s0; goto t0;}

int XX, AA, BB, CC, DD, EE;

#define ZERO_COUNTS XX = AA = BB = CC = DD = EE = 0;

#define INCREMENT(COUNT) XX++; COUNT++;

int main (void) {

ZERO_TAPE;

ZERO_COUNTS;

A:

INCREMENT(AA);

INSTRUCTION(1, R, B, 1, L, C);

B:

INCREMENT(BB);

INSTRUCTION(1, R, C, 1, R, B);

C:

INCREMENT(CC);

INSTRUCTION(1, R, D, 0, L, E);

D:

INCREMENT(DD);

INSTRUCTION(1, L, A, 1, L, D);

E:

INCREMENT(EE);

INSTRUCTION(1, R, H, 0, L, A);

H:

printf("%s | %d | %d %d %d %d %d\n", PROG, XX, AA, BB, CC, DD, EE);

}On my feeble laptop, this takes half a second to compile and run, which is quite an improvement.

Too Many Machines

Fast though it may be, that code is not general-puprose. It runs exactly one program, or equivalently, it models exactly one machine. Either way, it isn’t all that useful. How can a whole list of Turing machines be run in this manner?

My first idea was to mass-produce single-purpose machines as follows. Write a Python script containing a template of the C program above with holes for the instructions that reads in and parses a Turing machine string, fills in the holes, and spits out a complete C program. Dump that output into a temp file, pass the file to the C compiler, then run the resulting executable. Do that over a list of Turing machine strings. Coordinate the process with a simple shell script:

cat tm-list.txt | while read tm_string; do

python tm-2-c.py "$tm_string" > temp.c

cc temp.c -o temp

./temp

doneThis idea sounded good in my head, but turned out to be a spectacular failure. Within an hour, my laptop got hot, like I-would-have-sustained-injuries-if-it-had-been-on-my-lap hot, and for some reason the fan wasn’t turning on. It was also slow, so an enormous amount of effort was being expended with nothing to show for it.

A Programmable Turing Machine

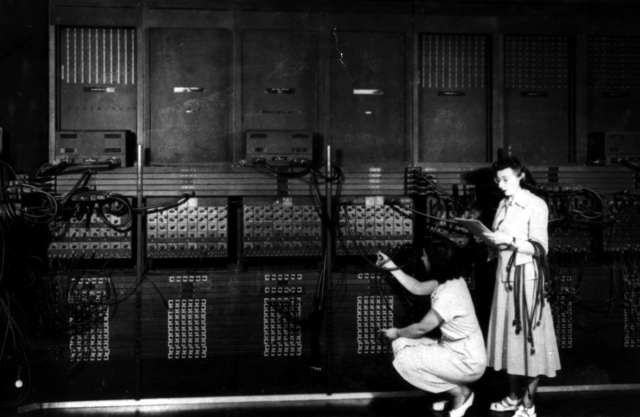

Instead of a single-purpose machine with some fixed instructions burned into it or whatever, what if the instructions were configurable? There would be just one machine, and it could be programmed not to simulate another machine, but to do just exactly what that machine would do. The mental picture I have is like one of those gigantic early computers with a bunch of toggles and switches, the kind of machine that was typically operated by women.6

It isn’t hard to see how the program above could be generalized, but there is a technical snag when implementing it in C. In standard C, goto targets (or “labels”) must be known at compile time. But the Turing machine to be executed won’t be known until runtime, and so neither will its control flow. One way to get around this constraint is to use GCC’s labels-as-values extension.7 This allows for passing around label addresses as values, putting them into variables, etc. With that and a little input handling, a programmable Turing machine is straightforward:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define TAPE_LEN ((100000 * 2) + 10)

unsigned int POS;

unsigned int TAPE[TAPE_LEN];

#define ZERO_TAPE \

POS = TAPE_LEN / 2; \

for (int i = 0; i < TAPE_LEN; i++) { \

TAPE[i] = 0; \

}

#define L POS--;

#define R POS++;

#define ACTION(c, s, t) { \

TAPE[POS] = c - 48; \

if (s - 76) { R } else { L }; \

goto *dispatch[t - 65]; \

}

#define INSTRUCTION(c0, s0, t0, c1, s1, t1) \

if (TAPE[POS]) \

ACTION(c1, s1, t1) \

else \

ACTION(c0, s0, t0)

unsigned int XX, AA, BB, CC, DD, EE;

unsigned int PP = 0;

#define ZERO_COUNTS XX = AA = BB = CC = DD = EE = 0; PP++;

#define INCREMENT(COUNT) XX++; COUNT++;

int c0, c1, c2, c3, c4, c5,

c6, c7, c8, c9, c10, c11,

c12, c13, c14, c15, c16, c17,

c18, c19, c20, c21, c22, c23,

c24, c25, c26, c27, c28, c29;

#define READ(VAR) if ((VAR = getc(stdin)) == EOF) goto EXIT;

#define LOAD_PROGRAM \

READ(c0); READ(c1); READ(c2); READ(c3); READ(c4); READ(c5); \

READ(c6); READ(c7); READ(c8); READ(c9); READ(c10); READ(c11); \

READ(c12); READ(c13); READ(c14); READ(c15); READ(c16); READ(c17); \

READ(c18); READ(c19); READ(c20); READ(c21); READ(c22); READ(c23); \

READ(c24); READ(c25); READ(c26); READ(c27); READ(c28); READ(c29); \

getc(stdin);

int main (void) {

static void* dispatch[] = { &&A, &&B, &&C, &&D, &&E, &&F, &&G, &&H };

INITIALIZE:

ZERO_COUNTS;

ZERO_TAPE;

LOAD_PROGRAM;

A:

INCREMENT(AA);

INSTRUCTION(c0, c1, c2, c3, c4, c5);

B:

INCREMENT(BB);

INSTRUCTION(c6, c7, c8, c9, c10, c11);

C:

INCREMENT(CC);

INSTRUCTION(c12, c13, c14, c15, c16, c17);

D:

INCREMENT(DD);

INSTRUCTION(c18, c19, c20, c21, c22, c23);

E:

INCREMENT(EE);

INSTRUCTION(c24, c25, c26, c27, c28, c29);

H:

printf("%d | %d | %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c %c%c%c | %d %d %d %d %d\n",

PP, XX,

c0, c1, c2, c3, c4, c5,

c6, c7, c8, c9, c10, c11,

c12, c13, c14, c15, c16, c17,

c18, c19, c20, c21, c22, c23,

c24, c25, c26, c27, c28, c29,

AA, BB, CC, DD, EE);

goto INITIALIZE;

EXIT:

printf("done\n");

exit(0);

F:

G:

goto EXIT;

}On my feeble laptop, this thing burns through Pascal Michel’s list of the 23 longest-running 5-state Turing machines in under 4 seconds.

Conclusion

The programmable Turing machine model is both faster than the simulator model and affords a more authentic expression of computational processes. I therefore conclude that Turing machines are programmable, and the appropriate name for Turing machine representations is “program”.

Discussion Questions

- What format does the programmable Turing machine expect for its programs?

- The programmable Turing machine only runs 5-state 2-color programs. Can it be extended to handle other cases?

- What exactly went wrong with the “mass production” strategy? Could it be salvaged into something workable?

- Why did the “mass production” strategy make the author’s laptop so hot?

- Is it ethical to write nonstandard C?

- Why doesn’t standard C permit putting labels into variables?

Programming Exercises

- Implement

1RB 1LC 1RC 1RB 1RD 0LE 1LA 1LD 1RH 0LAdirectly (that is, without any mediating structure) in Scheme. - Implement the programmable Turing machine in Scheme.

- Implement a Turing machine simulator in Python that is faster than the author’s.

Footnotes

1 Martin Davis put it this way:

Before Turing the general supposition was that in dealing with such machines the three categories, machine, program, and data, were entirely separate entities. The machine was a physical object; today we would call it hardware. The program was the plan for doing a computation, perhaps embodied in punched cards or connections of cables in a plugboard. Finally, the data was the numerical input. Turing’s universal machine showed that the distinctness of these three categories is an illusion. A Turing machine is initially envisioned as a machine with mechanical parts, hardware. But its code on the tape of the universal machine functions as a program, detailing the instructions to the universal machine needed for the appropriate computation to be carried out. Finally, the universal machine in its step-by-step actions sees the digits of a machine code as just more data to be worked on. This fluidity among these three concepts is fundamental to contemporary computer practice.

2 In particular, there are the so-called “4-tuple” and “5-tuple” definitions. The 5-tuple definition is the standard for the Busy Beaver competition, and it’s what is used in this post.

3 Of course, a Python program is run by an interpreter, so a simulator written in Python is a program that runs a program that runs a program. The same goes for any “interpreted language”.

4 This reason will only be compelling to you if you are some kind of hippie weirdo, like me.

5 If anyone has a general-purpose Turing machine simulator written in Python that can do better, I would love to see it.

6 See Top Secret Rosies: The Female “Computers” of WWII.

7 In standard C, this same logic could be expressed with a switch statement, but that is a little too close to the mediative simulation approach for my taste. It’s also slower.