A Formal Theory of Spaghetti Code

The Spaghetti Code Conjecture (SCC) says that Busy Beaver programs – the longest-running Turing machine programs of a given length – ought to be as complicated as possible. This was first proposed by Scott Aaronson:

A related intuition, though harder to formalize, is that Busy Beavers shouldn’t be “cleanly factorizable” into main routines and subroutines – but rather, that the way to maximize runtime should be via “spaghetti code,” or a single n-state amorphous mass.

I think SCC is probably false, and other people think it must be true. But what, precisely, does it mean? What exactly is “spaghetti code”? As Aaronson pointed out, the conjecture was only stated at the intuitive level and hasn’t been formalized. What’s needed is a formal theory of spaghetti code: an effective procedure that will determine of a given Turing machine program whether (or to what extent) the program is spaghetti.

Well, happy day: just such a theory emerged recently from a discussion between me and Shawn Ligocki after his discovery of a new 5-state Beeping Busy Beaver champion.

Given an N-state K-color TM program, consider the program’s control flow graph. This is a directed graph with N nodes and K arrows, with nodes corresponding to program states and arrows corresponding to state transitions. We will subject the graph to a graph reduction procedure. Apply the following transformations until no more changes can be made:

- Purge all nodes with no outbound arrows.

- Delete all duplicate arrows.

- Delete all self-pointing arrows.

- Inline any node with just one exit point.

- Inline any node with just one entry point.

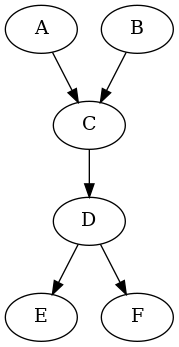

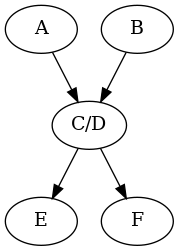

Steps 4 and 5 refer to “inlining” a node. This means deleting the node and giving its arrows to the nodes that reach it. The idea here is that we really only care about branching, and non-branching sequences don’t matter. For example, consider the first graph below. Node C can be reached from either A or B, and D can go to either E or F. These are branches. But C never goes anywhere but D, and so we might as well join them into one conglomerate node:

Anyway, you start with the program’s full control flow graph, then apply those reduction steps until no more changes can be made. Call whatever is left over the kernel of the graph. How many nodes are left in the kernel compared to how many nodes were in the original graph? This, I claim, constitutes some kind of meaningful measure of program complexity. A larger kernel means a more complicated program, and a smaller kernel means a simpler one. In particular, a graph that cannot be reduced at all can be considered utter spaghetti and a graph that can be eliminated completely can be considered thoroughly well-structured.

An important caveat to keep in mind is that this approach works best when states are many and colors are few. Here’s a fact: every graph of just two nodes can be reduced to nothing. This is because once the reflexive arrows are cut, the two nodes each have no more than on entry and exit (to the other node), and so all remaining arrows can be cut. This is true irrespective of how many arrows there were to begin with. So by the lights of this theory, every 2-state gajillion-color program is simple. Obviously that is not the case, and this shows a limitation to the theory.

With all this in mind, we can restate the Spaghetti Code Conjecture formally: the control flow graph of (sufficiently long) Busy Beaver programs ought to be at least partially irreducible.

Do the facts support this claim? No, they do not! The following programs are all totally reducible and therefore anti-spaghetti:

- The BBB(4) champion (quasihalts in 32,779,478 steps)

- The BB(5) champion (halts in 47,176,870 steps)

- The BBB(5) champion (quasihalts in > 10502 steps)

- The BB(6) champion (halts in > 36,534 steps)

Pascal Michel maintains a list of historical Busy Beaver champions. Of the 23 top-scoring 5-state halting programs, just two of them (#2 and #23) are partially irreducible; of the 12 top-scoring 6-state halting programs, just four are partially irreducible (#2, #10, #11, and #12). Finally, Shawn Ligocki maintains a list of the 20 top-scoring 5-state quasihalting programs. Not a single one of these is even partially irreducible.

Thus there is no concrete evidence at all that the Spaghetti Code Conjecture is true. All available evidence points towards the opposite conclusion, which we might call the Clean Code Conjecture (CCC): that all Busy Beaver champion programs are well-structured and fully graph-reducible. (A better name maybe would be “Structured Code Conjecture”, but then we would have a collision of initials.)

You can point all this out to people and they will still insist that the SCC must be true. Why? As far as I can tell, the only arguments in favor of SCC rely on dismissing all the available evidence. This is done in two ways.

The first is to say that short programs just can’t be all that complex, and therefore short programs don’t consistute real evidence. Sure, the BBB(4) champion may be simple, but that’s just because all 4-state programs are trivially simple, and the SCC only applies for “sufficiently long” programs.

The problem with this argument is that it assumes that 4-state programs cannot be complex, and this is stated as if it were some obvious logical truth. But it isn’t a logical truth – it amounts to an empirical claim, and in fact it’s a false one. There are indeed complex programs of just four states whose behavior cannot be easily described. I’ve previously discussed a program discovered by Boyd Johnson that enters into Lin recurrence after 158,491 steps with a shocking period of 17,620. This program has an irreducible 3-node kernel, and is therefore spaghetti by the lights of our theory. So 4-state programs can be spaghetti, and therefore the fact that the BBB(4) champion is not constitutes evidence against SCC.

The second argument for dismissing the available evidence is that the means for discovering champions are biased in favor of simple programs. The best Turing machine simulator that I am aware of is the one written by Shawn and Terry Ligocki. It can analyze a running program and determine if it exhibits Collatz-like behavior; if this behavior is detected, it can be extrapolated out to extreme lengths. This is how Shawn discovered, for instance, the current BBB(5) champion.

But if a program does not exhibit such behavior, the simulator will not find it. This means that the availble evidence is overwhelmingly colored by a selection bias in favor of Collatz-like programs, and especially those that are amenable to analysis. Simpler programs are more amenable to analysis than more complex ones, and thus we should expect simpler programs to be easier to find. There is an observable universe of programs, and it does not encompass the whole of program space.

This is a disquieting state of affairs, to be sure, and it should be kept in mind at all times when discussing these uncomputable functions. Still though, this isn’t an argument in favor of the SCC; it’s just an argument that the available evidence isn’t all that compelling, and we should keep an open mind about counterexamples.

Such skepticism can be applied to the Collatz conjecture. According to Wikipedia, the Collatz conjecture has been verified up through about 1020. Well, whoop-de-doo! Any number that we humans can actually reach is by definition puny; the “observable universe” of numbers just doesn’t reach very far. It’s even been proved that a Collatz counterexample must have certain striking properties, like an enormously long orbit. These proofs are in effect proofs that we will not be able to find a counterexample, even if there is one.

Is this skeptical attitude reasonable? There’s definitely something to be said for it, although taken to the extreme it takes on an almost conspiratorial that’s-what-they-want-you-to-think quality. In any case I find myself unmoved when it comes to the SCC.

Discussion Questions

- Has this graph reduction procedure been discussed before? If so, what is it called?

- Would you join a club that would accept you as a member?

- What might exist outside the observable universe of programs?

- Does the selection bias argument apply to all open conjectures (Goldbach, etc), or just some of them?