Maybe the Spaghetti Code Conjecture is False

The Spaghetti Code Conjecture says that Busy Beaver programs ought to be, in some sense, as complicated as possible. Scott Aaronson puts it this way:

Busy Beavers shouldn’t be “cleanly factorizable” into main routines and subroutines—but rather, the way to maximize runtime should be via “spaghetti code,” or a single n-state amorphous mass.

This vague conjecture was formulated as a sort of generalization of a more narrowly-scoped conjecture by Joshua Zelinsky. This conjecture says that the control flow graph of a Busy Beaver program ought to be strongly connected (i.e. that every node should be reachable from every other node). One concrete way to interpret the Spaghetti Code Conjecture is as a broad set of predictions about Busy Beaver graphs – that the entry and exit connections of nodes ought to be dispersed, or that reflexive nodes should be absent (or present), etc.

When I first heard the Spaghetti Code Conjecture, I thought it sounded like a good idea. I even had hopes that it could be used as the basis for a new form of program search. But I have come around to the belief that not only is the Spaghetti Code Conjecture of no practical use, it isn’t even true.

First, consider the naive way to search over Turing machine programs of some class, namely just enumerating all of them. This gets infeasiable fast. My early Beeping Busy Beaver results actually came from this approach, and it was miserable. There are just too many programs to deal with, and many of them are either duplicates or junk.

Then I starting thinking about the Strongly Connected Graph Conjecture, and that led me to a search technique I call graph decoration. Instead of enumerating programs directly, first enumerate graphs pursuant to various conjectures (strong-connectedness, etc), and then “decorate” those graphs with print and shift instructions. This ensures that only programs with the expected graph properties are generated. The graph decoration method worked, and it turned up a new champion program.

After that I tried to push the Spaghetti Code Conjecture further and search over increasingly restricted graphs. Specifically, I thought that Busy Beaver graphs should have no topographically distinct features, and every node should be as indistinguishable as possible. Some interesting programs turned up this way, but no champions.

Eventually I managed to implement the classic tree generation method. This technique was developed by Allen Brady in his 1964 dissertation, and it has been used to find just about every current Busy Beaver champion. Instead of enumerating programs outright, start with a program whose only defined instruction is A0 -> 1RB. Then run it until an undefined instruction is reached. Generate all the possible instructions that could be used (ignoring isomorphic duplicates), and then recursively run the procedure on all the programs that result from extending the original with the generated instructions. (All along, stop if certain termination conditions are met.)

Brady’s algorithm (as we might call it) is a much, much better method for generating programs than graph decoration. Although it takes longer to execute, because it requires actually running programs, it yields several orders of magnitude fewer programs. Fewer programs can be run for longer, and that enables finding longer-running champions. And indeed, when I switched to using tree generation, I found one.

Here’s a table to summarize the differences between enumeration techniques according to their use in 4-state 2-color search. “Yield” is how many programs were generated; “Search” is how many steps the resulting programs could be run for; and “Champ” is the stop-count for the champion programs discovered using each method.

| Method | Yield | Search | Champ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | 230 | 214 | 2,819 |

| Graph decoration | 224 | 221 | 66,349 |

| Tree generation | 217 | 228 | 32,779,478 |

Okay, so tree generation is much better than graph decoration. But maybe the various graph conjectures could still be put to use as a filter? Brady’s algorithm could be used to generate a list of programs, and then all of the ones without, say, strongly connected graphs could be dropped. Well, I looked into that, and it turns out that almost every program generated by Brady’s algorithm already has a strongly connected graph.

I believe this allows us to draw two conclusions:

- The Strongly Connected Graph Conjecture is definitely true.

- It is useless for improving search.

Another way to look at it is to say that the conjecture is not as strong as it might initally appear. It doesn’t tell us anything that wasn’t already known from tree generation. In fact, it seems weak enough that it might even be provable.

The Strongly Connected Graph Conjecture is just one piece of the broader Spaghetti Code Conjecture. I’ve argued that the former is true, and I claim now that the latter might be false. To see why, consider the 4-state 2-color Beeping Busy Beaver champion:

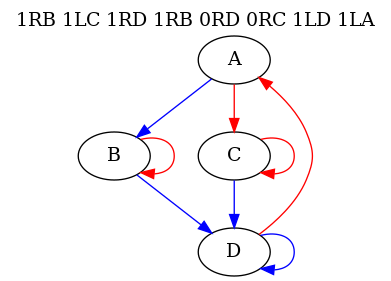

1RB 1LC 1RD 1RB 0RD 0RC 1LD 1LAThis program is definitely not spaghetti. Look at its control flow graph (where a blue arrow means a transition from 0 and red means a transition from 1):

One interpretation of the Spaghetti Code Conjecture says that a Busy Beaver graph ought to be featureless. But this program has a variety of distinctive features. Just from eyeballing the graph one can tell the roles of the different nodes:

- Node

Ais a dispatcher, directing control to eitherBorC. - Nodes

BandCeach execute while-loops on1. Since there are only ever finitely many marks the tape, these loops are guaranteed to terminate. - Node

Dexecutes a while-loop on0. There are infinitely many blank squares on the tape, so this loop has the potential to run forever. One might guess on account of this power thatDacts as a driver for the program, and indeed it does.

Far from being spaghetti, this program is a model of elegance. If you studied it long enough, you would be able to figure out exactly how it works, and maybe even how to modify it with confidence. I wish I could say that I wrote it, but I didn’t. I just came across it one morning, like a peasant farmer finding an ancient tablet in the field.

So if it isn’t complicated spaghetti code, then how does it run for so long? Shawn Ligocki figured out that the program implements the following Collatz-like function (L: ℕ -> ℕ):

L(3k) = 0

L(3k + r) = L(5k + r + 3)–> JUICY OPEN PROBLEM <–

- Is L total? That is, does it always terminate?

- If you can prove it one way or the other, please contact me at your earliest convenience.

At first glance, there is nothing remarkable about L. But consider L(2):

2 | 5 | 10 | 19 | 34 | 59 | 100 | 169 | 284 | 475 | 794 | 1325 | 2210 | 3685 | 6144L(2) has an orbit of 14 iterations. That is a long orbit for a short input, and it’s how this program wins BBB(4). There is no trickery; it simply takes advantage of this peculiar mathematical fact.

This is reminiscent of the lesson of the Bigger Number Game:

Place value, exponentials, stacked exponentials: each can express boundlessly big numbers, and in this sense they’re all equivalent. But the notational systems differ dramatically in the numbers they can express concisely…The key to the biggest number contest is not swift penmanship, but rather a potent paradigm for concisely capturing the gargantuan.

One way to think about the Busy Beaver game is as a formalization of the Bigger Number Game, with all the Turing machine programs of a certain length competing against each other. It’s concepts rather than tricks that take the day in the Bigger Number Game, and the BBB(4) champion wins because of the math that it “knows”. Why should it be any different for longer programs? It could be that in all cases the champion programs are relatively straightforward programs that exploit exotic and obscure mathematical facts.

We can also look at the results of the C Bignum Bakeoff from 2001:

The object of the BIGNUM BAKEOFF is to write a C program of 512 characters or less (excluding whitespace) that returns as large a number as possible from main(), assuming C to have integral types that can hold arbitrarily large integers.

The winner of this contest turned out to be a sort of Busy Beaver variant:

The final and winning entry…diagonalizes over the Huet-Coquand `calculus of constructions’. This is a highly polymorphic lambda calculus such that every well-formed term in the calculus is strongly normalizing; or, to put it another way, a relatively powerful programming language which has the property that every well-formed program in the language terminates.

The first runner-up was submitted by none other than Heiner Marxen, who co-discovered the BB(5) champion in 1989. This entry implements a variant of the Goodstein function, a total function that Peano arithmetic can’t prove to be total.

So the Bigger Number Game and the Bignum Bakeoff both suggest that Busy Beaver champions will win by theory rather than by tricks, and the BBB(4) champion program confirms it. Maybe the Spaghetti Code Conjecture is false. But what if this is unjustified extrapolation, and these early Busy Beaver results can’t tell us anything about later ones? As Timothy Chow says:

That a four-state busy beaver is simple looks to me like the law of small numbers at work. A single strand of spaghetti that is 4 cm long can’t get too tangled up.

Of course we should be skeptical of any kind of broad conclusion about general Busy Beaver behavior. A few facts can be proved, but the Spaghetti Code Conjecture has not been proved either way, and this post is utterly speculative.

But Chow’s second argument is that the 4-state champion is simple becuase it can’t but be, with the implication that complexity only enters the picture for longer programs. This is not the case, and in fact we can exhibit an explicit counterexample:

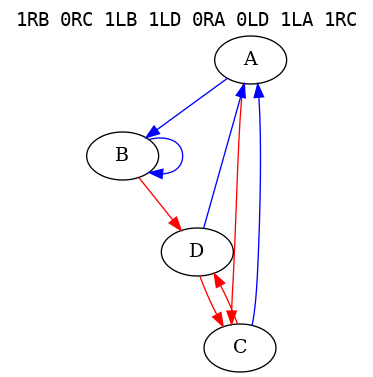

1RB 0RC 1LB 1LD 0RA 0LD 1LA 1RCThis program was discovered by Boyd Johnson. It runs for 158491 steps before entering in Lin recurence with period of 17620 steps. Its control flow graph is a living nightmare:

I don’t know what this program does, but it definitely does something of interest.

–> ESOTERIC OPEN PROBLEM <–

- What does this program do?

Boyd’s discovery shows that simplicity is not inevitable even in the space of 4-state 2-color programs. So the BBB(4) champion could but complicated, but it isn’t. Therefore the Spaghetti Code Conjecture is false in this case, but not trivially false.