Structured Programming for Busy Beavers

…programs in machine language, devoid of structure; or, more precisely, it is difficult for our eyes to perceive the program structure.

– Knuth

Busy Beaver programs are complicated. In some sense they are as complicated as they could possibly be. They have even been described as “spaghetti code”. But what kind of programs are they? What do they do?

Part of the difficulty with understanding Busy Beaver programs is the code in which they are expressed is somewhat obscure. Here we must distinguish between the Turing machine hardware and the Turing machine language. The Turing machine itself is a device with a single tape, infinite in both directions, and a read/write head that travels back and forth, reading and writing the cells of the tape. A low-level language is used to write programs for the machine. (As usual, we take the view that a Turing machine is a programmable device, a real computer.) A program written in this language consists of a certain number of states, each of which contains directions for each possible color that can be read off from the tape. Each direction is made up of three instructions: a color to print, a left or right shift, and the next state to transition to. On each machine cycle one of these triple instructions is executed.

“State” is a murky word. It suggests that the machine shifts from one of a fixed number of modes to another, like a bicycle shifting gears. Turing himself referred to these as “m-configurations”, although he did also mention that a human computer would have some finite number of “states of mind” when undertaking a computation. In any case, the “state” seems to belong to the machine rather than to the program. Rado, the inventor of the Busy Beaver game, referred to states as “cards” to emphasize that the core issue is control flow within a program and not the operational details of a machine.

To put a point on it, we might also refer to states as “labels”, as in the things that you goto. Imagine a C program with n labels with a switch on k colors under each one. That gives a concrete idea of the meaning of the “length” of a Turing machine program. In fact, there is no need to imagine. Here is the 3-state 2-color Busy Beaver champion, which runs for 21 steps before halting:

1RB 1LH 1LB 0RC 1LC 1LAAssuming the appropriate machine operation instructions are available, this Turing machine program can be implemented directly in C (and this gloss should suffice to explain the notation above):

#include "machine.h"

int main(void)

{

A:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

RIGHT;

goto B;

}

else

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto H;

}

B:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto B;

}

else

{

ERASE;

RIGHT;

goto C;

}

C:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto C;

}

else

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto A;

}

H:

PRINT_STEPS;

}This is a fully unstructured program, the kind of thing that was famously denounced by Dijkstra. Knuth came to the defense of the goto statement, but he would not have defended a program like this. He quotes from Landin:

There is a game sometimes played with Algol 60 programs – rewriting them so as to avoid using

gotostatements. It is part of a more embracing game – reducing the extent to which the program conveys its information by explicit sequencing. … The game’s significance lies in that it frequently produces a more “transparent” program – easier to understand, debug, modify, and incorporate into a larger program.

This game can be played with Busy Beaver programs as well. Two basic techniques come in handy: rolling up loops and inlining. I don’t know if there is a better name than “loop roll-up”, but what I mean is the conversion of a label into an explicit while loop. Consider label B above:

B:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto B;

}

else

{

ERASE;

RIGHT;

goto C;

}If the scanned square is blank, control remains with B; otherwise it passes to C. But this is just to say that the machine will print and move left while the scanned square is blank, and then it will erase and move right and go to C. This can be rewritten as a while loop, and the same transformation can be applied to C:

B:

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

LEFT;

}

ERASE;

RIGHT;

goto C;

C:

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

LEFT;

}

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto A;At this point there is an unconditional jump to C at the end of B. But that jump comes directly before the introduction of the C label, so it can be eliminated in favor of fallthrough. That was the last reference to label C, so in fact the label can be done away with entirely, with B absorbing its body. Now there is just one jump to B, in the body of A. The entire body of B can therefore be inlined directly at its “call site”. Finally, A reveals itself to also be a simple loop. A little rearranging gives the final goto-less program (with annotations of the original labels):

while (BLANK) {

// A0

PRINT;

RIGHT;

// B0

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

LEFT;

}

// B1

ERASE;

RIGHT;

// C0

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

LEFT;

}

// C1

LEFT;

}

// A1

LEFT;Is this more “transparent” than the original? It’s still hard to say what it “does” or “why” it does it, but the block structure is now apparent. B sits in the middle of the main loop and C is at the end. I wouldn’t be able to modify this program in a predictable manner, but that was already well true.

Note that there is no longer any explicit halt instruction. If the scanned square is blank at the top of the main loop, the body of the loop is executed, and otherwise the program ends (after one more shift). There are no explicit break or continue statements, so this program is well-structured.

Let’s look at one more example, the 4-state 2-color Blanking Beaver champion: 1RB 0LC 1LD 0LA 1RC 1RD 1LA 0LD. In this case, the program has no halt instruction to begin with; instead, the machine will halt when the tape becomes blank, and this will happen after 66345 steps.

As before, we start with the unstructured code:

A:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

RIGHT;

goto B;

}

else

{

ERASE;

LEFT;

goto C;

}

B:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto D;

}

else

{

ERASE;

LEFT;

goto A;

}

C:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

RIGHT;

goto C;

}

else

{

PRINT;

RIGHT;

goto D;

}

D:

if (BLANK)

{

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto A;

}

else

{

ERASE;

LEFT;

goto D;

}Things initially proceed as before. Labels C and D are rolled up into loops, and then B and C are inlined.

A:

if (BLANK)

{

// A0

PRINT;

RIGHT;

if (BLANK)

{

// B0

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto D;

}

else

{

// B1

ERASE;

LEFT;

goto A;

}

}

else

{

// A1

ERASE;

LEFT;

// C0

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

RIGHT;

}

// C1

PRINT;

RIGHT;

goto D;

}

D:

// D1

while (!BLANK) {

ERASE;

LEFT;

}

// D0

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto A;This time D can be inlined, but it has to be copied to two separate call sites.

A:

if (BLANK)

{

// A0

PRINT;

RIGHT;

if (!BLANK)

{

// B1

ERASE;

LEFT;

goto A;

}

else

{

// B0

PRINT;

LEFT;

// D1

while (!BLANK) {

ERASE;

LEFT;

}

// D0

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto A;

}

}

else

{

// A1

ERASE;

LEFT;

// C0

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

RIGHT;

}

// C1

PRINT;

RIGHT;

// D1

while (!BLANK) {

ERASE;

LEFT;

}

// D0

PRINT;

LEFT;

goto A;

}Now there is only one label, A, and all the branches terminate with goto A. This means A is a loop and the label can be rolled up. There’s not even a need for explicit continue statements; the goto statements can simply be dropped. But notice that both branches end up jumping back to the top. Previous examples of loop roll-ups only jump back through one branch, and that branch could be used as the loop’s termination condition. If both branches jump back, then neither can be used as a termination condition, and we end up with a genuine unbounded loop:

while (1) {

if (BLANK)

{

// ...

}

else

{

// ...

}

}Such a harsh loop suggests that we are approaching undecidability. Basically the program says: apply this complicated transformation function to the tape over and over and eventually the tape will get blanked. There isn’t the slightest hint of how long this should take, or under what circumstance the loop will terminate, or why it will work. It does work, but only as if by magic. You might think that while (1) could be replaced by while (TAPE_NOT_BLANK), but you would be wrong; the point at which the blank tape is detected is in the middle of the loop, not at the top.

After “refactoring” D and making a few more tweaks, the program assumes its final form:

while (1) {

if (BLANK)

{

// A0

PRINT;

RIGHT;

if (!BLANK) {

// B1

ERASE;

LEFT;

continue;

}

// B0

PRINT;

LEFT;

}

else

{

// A1

ERASE;

LEFT;

// C0

while (BLANK) {

PRINT;

RIGHT;

}

// C1

PRINT;

RIGHT;

}

// D1

while (!BLANK) {

ERASE;

LEFT;

}

// D0

PRINT;

LEFT;

}Exercises

-

Implement

machine.hand use it to run these C programs. (Hint: use macros.) -

Compare the analysis of the Busy Beaver programs with the analysis of “signed char lotte”.

-

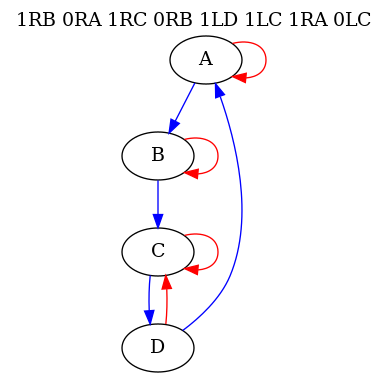

Examine the control flow graph for the 4-state 2-color Blanking Beaver champion and correlate its features with the code above:

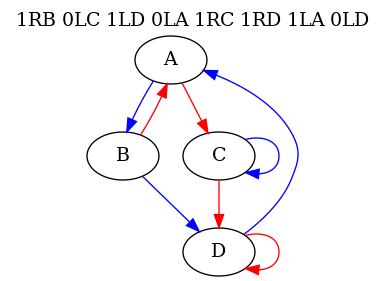

- The 4-state 2-color Recurrent Beaver champion runs for 158491 steps before entering into Lin recurrence with a period of 17620 steps. Use its control flow graph to predict the structure of its code:

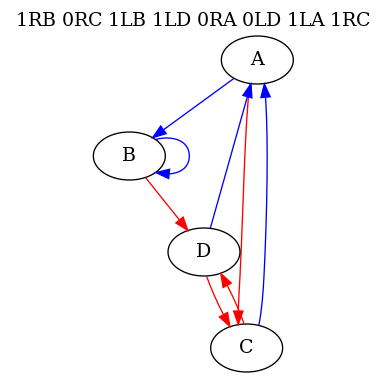

- The 4-state 2-color Periodic Beaver champion runs for 7170 steps before entering into Lin recurrence with a period of 29117 steps. Use its control flow graph to predict the structure of its code: