A History of Busy Beaver Hardware

The Busy Beaver question asks how long a Turing machine program of a fixed length can run before halting (or more generally, reaching some particular condition). The question was first posed in 1962. It didn’t take long for researchers to realize that solving this question for any non-trivial case would require the use of computers. Sometimes they named the specific hardware they used. This post is a list of all the computers I have seen mentioned in the literature.

IBM 7090

[W]ith considerable help from the IBM 7090 (and considerable work on a computer program) it was found that 𝛴(2) = 4; but S(2) is yet unknown.

- Tibor Rado, “On a simple source for non-computable functions”, 1962

The fully-transistorized system has computing speeds six times faster than those of its vacuum-tube predecessor, the IBM 709, and seven and one-half times faster than those of the IBM 704. Announced in December, 1958, the first 7090 was installed in December, 1959.

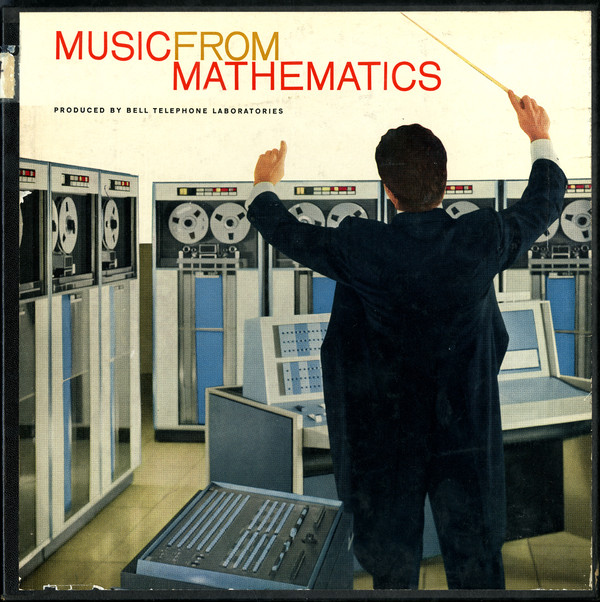

The IBM 7090 was prominently featured in the movie Hidden Figures. It was also used in a 1961 album produced by Bell Labs called Music from Mathematics. I love weird old music and weird computer music, but I have to say that this album is not very good.

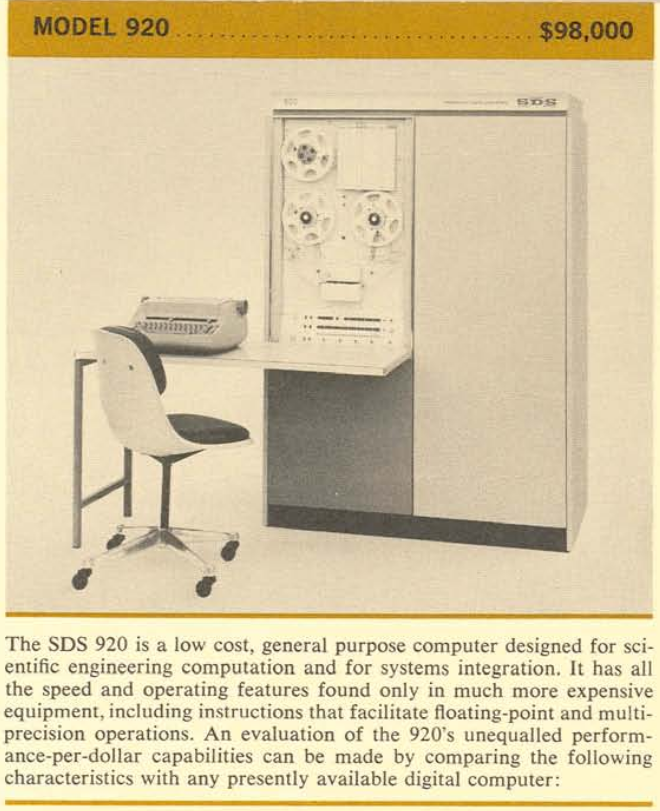

SDS 920

The program as written for the SDS 920 computer encompasses nearly 2,000 instructions…

- Allen Brady, PhD dissertation, 1964

In the old days, finding and getting access to a computer was not easy. Brady had to drive 90 miles from Oregon State University to use the SDS 920 at the Oregon Regional Primate Center. This was located, of all places, in a town called Beaverton.

It was on the SDS 920 that Brady found the BB(4) champion program, which halts after 107 steps. He also used the 920 to develop the tree generation method. Here is what Brady had to say in 1964 about the use of high-level programming languages:

While use of one of the present day scientific programming languages might have been possible and would have saved the effort required to learn the “machine language”, it would not have simplified the logic of the program in any material way and would almost certainly have decreased the efficiency of execution to such a degree that the program could not have been run economically. There in fact do not seem to be any progamming languages in use today which might have aided significantly in the writing of this program.

IBM 1620

[A] program to simulate the Turing machine was written for the IBM 1620 computer. This computer was chosen primarily for its availability…

- Allen Brady, PhD dissertation, 1964

In a hilariously shady remark, Brady says that the IBM 1620 was “chosen primarily for its availability”. This appears to capture the general feeling about the 1620; few reminiscences are fond:

[T]he 1620’s nickname was CADET (Can’t Add Doesn’t Even Try) because addition was accomplished using lookup tables [!!!] rather than adders (similarly for subraction and multiplication, and there was no DIVIDE instruction at all; division was done in software).

The 1620 multiplied and divided by using tables stored in memory. As you’d expect, a common and sophomoric stunt was to load the tables with corrupted values, making a friend’s program produce garbage.

IBM 360 model 65

Using an IBM 360 model 65 for this program was enough faster than previous work … that some progress could now be made toward exhausing the five-state problem.

- Donald Lynn, “New results for Rado’s sigma function for binary Turing machines”, 1971

Lynn was able to show that BB(5) ≥ 435. It’s now known that BB(5) ≥ 47,176,870. Lynn says: “All five-state runs were set so that 500 moves would be made before abandoning each machine as nonhalting…”

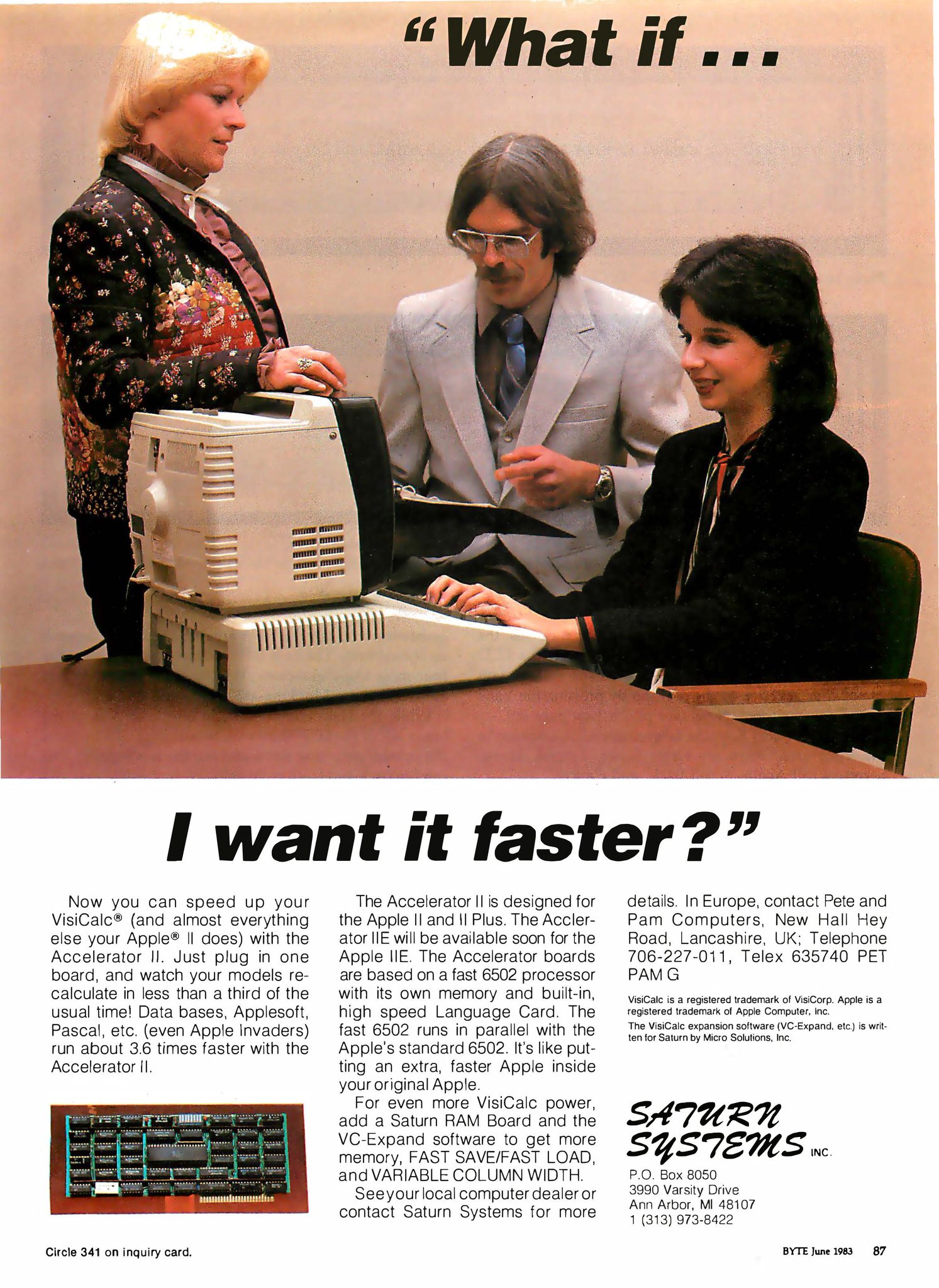

Apple II

All programming was done on a personal computer (Apple II, 6502 microprocessor at 1MHz, 47 K Bytes RAM), extended with 6809 microprocessor board (running at the same speed) for programming convenience; the program, written in 6809 machine language, was about 700 bytes long.

Uwe Schult, “Chasing the Busy Beaver”, 1982

Schult says that he ran his Busy Beaver search for 803 hours – over one full month straight. This search was conducted as part of a competition held among programmers in West Germany. He was able to show that BB(5) ≥ 134,467. It’s now known that BB(5) ≥ 47,176,870.