Emacs Lisp Challenge: flaky-if

SCENARIO: An Emacs user gets up and leaves the room, leaving their Emacs instance running and unattended. As a prank, you decide to overwrite the built-in if operator with another operator that is just like if except that it occansionally swaps its then- and else-clauses. How can this be done? Here are three challenges, in ascending order of difficulty, related to this flaky if.

Challenge #1

Implement flaky-if, which is just like if except that, say, 1% of the time it swaps its then- and else- clauses.

As a test, the following expression should evaluate to around 101:

(cl-loop

for _ from 1 to 1000

sum (flaky-if t 0 1))NOTE: This will not fulfill the goal of the prank, but it’s a good warmup for Challenge #2.

Challenge #2

Make the built-in if operator act the same way as flaky-if from Challenge #1 without screwing up the running Emacs instance.

As before, the following should evaluate to around 10:

(cl-loop

for _ from 1 to 1000

sum (if t 0 1))WARNING: Take heed of the italicized qualification. You can really jack up an Emacs session if you get this wrong, and that will quickly alert the mark that their computer has been tampered with.

Challenge #3

After Challenge #2, the built-in if operator is overwritten with the flaky version. Find some Elisp code which, when evaluated under the regime of the flaky if, behaves strangely but without being completely busted.

NOTE: “Completely busted” includes throwing a stack overflow error, or slowing to a crawl, or anything like that. Something should happen, and it should somewhat resemble the code’s intended behavior. This is an open-ended challenge. Feel free to change the 1% flip-rate to something like one-in-a-million.

Solutions

First, some review. The signature of the if operator is (if test then &rest else), and it is evaluated as follows. First the test expression is evaluated. If it comes out to non-nil, then then is evaluated and returned; otherwise, the zero or more else expressions are evaluated in sequence with the last one being returned if there is one or nil otherwise.

With normal function calls, each argument is evaluated exactly once at call-time. if doesn’t work like that, and so neither will flaky-if. The standard Lisp facility for defining function with different evaluation patterns is defmacro:

(defmacro flaky-if (test then &rest else)

...)defmacro defines a new function that acts as a compiler directive. Rather than receiving evaluated arguments, it receives its arguments unevaluated; that is, it receives Lisp code as arguments. The typical output of a macro is another Lisp expression which will itself get evaluted later. The macro function will contain logic to shuffle around its initial arguments, possibly evaluating any of them.

Macro definitions frequently employ backtick-comma-at notation. Whereas the quote operator ' returns a list whose elements are unevaluated, the backtick operator ` returns a list whose elements are evaluated if preceded with a comma ,, evaluated and spliced in if preceded with a comma-at ,@, and unevaluated otherwise.2

One way to define flaky-if would be to shuffle around the then and else blocks inside some if expression. But observe that the same effect could be achieved simply by negating the test expression. A function can be chosen at compile time to be attached to test; 1% of the time it will be a negating function, and the other 99% of the time it will be a function that does nothing.

(defmacro flaky-if (test then &rest else)

(let ((maybe-switch

(if (zerop (random 100))

'not

'identity)))

...))The final result of the macro needs to be a Lisp expression, so all that remains is to plug in the pieces:

(defmacro flaky-if (test then &rest else)

(let ((maybe-switch

(if (zerop (random 100))

'not

'identity)))

`(if (,maybe-switch ,test)

,then

,@else)))And that’s a solution to Challenge #1.

Challenge #2 is trickier. flaky-if relies on the builtin if, but if the goal is to redefine if, then that won’t be possible. (Or will it? Try it and see what happens.)

The thing that if is needs to be saved somewhere for use in the new if macro that will be defined. There are a lot of ways that you might think to do this, and most of them are wrong. One way that seems to work, and I don’t exactly understand how, is to take the function-value of the symbol if and store it in the function slot of some other symbol, say old-if. Then the new if macro can rely on old-if, which does the same thing as the builtin if, and the macro will otherwise look like the definition of flaky-if.

(setf (symbol-function 'old-if) (symbol-function 'if))

(defmacro if (test then &rest else)

(let ((maybe-switch

(old-if (zerop (random 100))

'not

'identity)))

`(old-if (,maybe-switch ,test)

,then

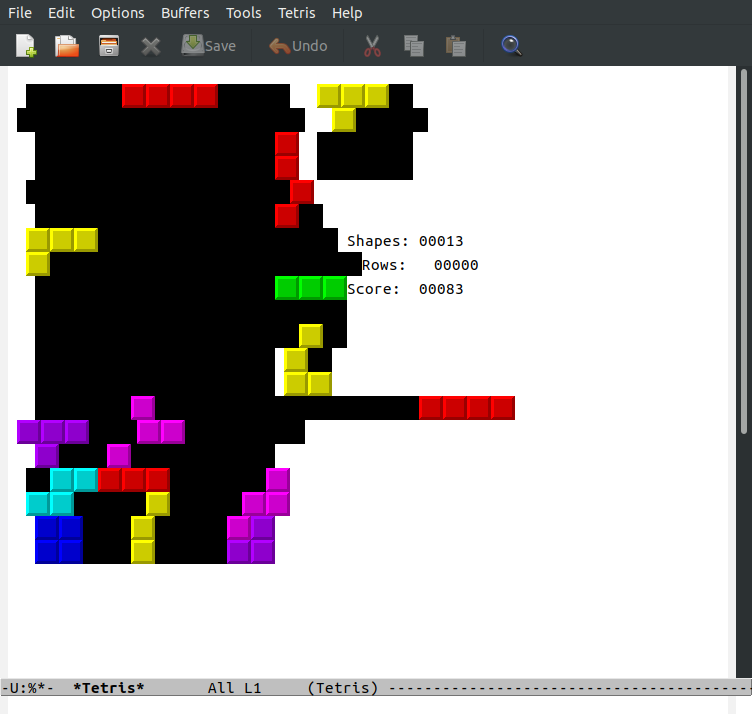

,@else)))For Challenge #3, I changed the random call in the if macro to (random 1000000) and then evaluated the file tetris.el. This resulted in something that looks like Tetris, but with some unusual collision detection:

Discussion Questions3

-

Can the

flaky-ifoperator be defined in a non-Lisp language? If so, how? If not, why not? -

Are there any other ways to solve Challenge #2?

-

Ben Bitdiddle’s answer to Challenge #1 is similar to the given solution, but it doesn’t work. What’s wrong with it? How can it be salvaged?

(defmacro flaky-if (test then &rest else)

(let ((maybe-switch

(if (zerop (random 100))

'not

'identity)))

`(if (funcall ,maybe-switch ,test)

,then

,@else)))- Alyssa P Hacker thinks that there must be something wrong with the given solution to Challenge #1. She proposes the following instead:

(defmacro flaky-if (test then &rest else)

`(let ((maybe-switch

(if (zerop (random 100))

'not

'identity)))

(if (funcall maybe-switch ,test)

,then

,@else)))Eva Lu Ator disagrees, saying that the two definitions are equivalent, and that Alyssa’s solution is actually a little slower. Who is right?

- Louis Reasoner finds it wasteful to call

randomon every invocation offlaky-if. Instead, he thinks it should suffice to call it just once at macro definition time:

(let ((flip (zerop (random 100))))

(defmacro flaky-if (test then &rest else)

`(if (funcall ',(if flip 'not 'identity) ,test)

,then

,@else)))What does his version of flaky-if do?

- The goal of this prank is ultimately to lead the mark into a debugging hell from which they may never return. The best solution, therefore, is the one that is hardest to debug. With that in mind, is it better to use a macro that behaves randomly at compile-time or at run-time? Does it make a difference if the mark is evaluating code interactively or byte-compiling? Is there a way to combine compile-time and run-time randomness to make the behavior even harder to debug?

Credits

The flaky if challenge was initially posed by Joe “begriffs” Nelson. The setf line in the solution to Challenge #2 was developed by Erik Anderson. Christopher “skeeto” Wellons raised some issues concerning byte-compilation.

Footnotes

1 (require cl-lib) first if needed.

2 As a quick check of understanding, evaluate the following expression:

(let ((x '(2 3 4)))

(list

'(1 x 5)

`(1 x 5)

`(1 ,x 5)

`(1 ,@x 5)))3 I can’t seem to get the number of this list right, but I don’t feel like delaying this post to fix it. It has something to do with the Org code blocks.