Book Review: The Little Typer

The Little Typer is the latest book in the Little Schemer series. If you haven’t heard of these books, check them out. They’re written as pseudo-children’s books, and each one illustrates a different fundamental programming concept using a series of dialogues. The topic of The Little Typer is dependent types, such as are used in languages like Coq and Idris, and their relationship with proofs.

Before going into any details, I’ll say that I loved The Little Typer. It’s a deep book, and it deals with a style of programming that you almost certainly have not seen before. It took me a long time to work through the material completely, but I consider that time well spent, and I’m a better programmer for it. If you are a programmer with any interest in logic or proof-oriented math, you should read this book.

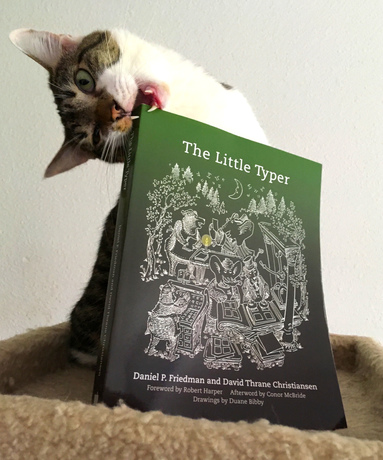

That said, if you don’t care about those things, you might find the book obscure and pointless. To get the perspective of a more “practically-minded” programmer, I asked my cat, Kemal, to review the book as well. He has a background as a sysadmin and got into programming through writing increasingly complicated Python scripts at work. His decidedly negative remarks are included below.

Now, on to the details. A dependent type is a type that is parameterized by a value. Lots of languages have types that are parameterized by other types, like List<T>, but those are not dependent types. Dependent types are parameterized by instances of types. The example that everyone uses (and I won’t be an exception) is the fixed-length list, usually called a vector. Instead of List<T> where T is some type, a vector looks like Vect<n, T> where T is some type and n is a nonnegative integer. Just as List<Char> and List<Int> are different concrete types, Vect<4, Char> (a list of four characters) and Vect<5, Char> (a list of five characters) are different concrete types.

The type signatures of functions can manipulate these values in unusual ways. Again, the most common example is a simple append function: given Vect<m, T> and Vect<n, T>, it produces Vect<m + n, T>. Take a good look at that signature, because it changes everything. In order to verify those types, the compiler needs to know how to do arithmetic. What’s more, in order to verify dependent types in general, the compiler needs to know how to do partial program evaluation.1

You can do some cool stuff with such a knowledgeable compiler. The Little Typer touches on three basic applications of dependent types.2

-

“Enhanced” types. That’s my expression, not the book’s. What I mean is types that encode more information than non-dependent types3. The

appendexample falls into this category. The compiler can catch type errors, but it can also catch the kinds of logic errors that would lead to lists of the wrong length being created. Another use of “enhanced” types is aheadfunction that will raise a compiler error when used on a list not known to be nonempty. -

Mathematical theorem proving. Dependent types are equivalent in expressive power to first-order logic, so it’s possible to create types that correspond to statements involving both universal and existential quantification. The Little Typer shows how to prove statements like “Every natural number is either even or odd”, i.e. “For every natural number n, either there is k such that n = 2k or there is k such that n = 2k + 1”.4

-

Program verification. This is like mathematical theorem proving, except that the theorems proved deal with the usual objects of programming rather than with math. As an example, the book develops two functions, one that converts lists to vectors and another that converts vectors to lists. Then a third function is developed that shows that a list which is converted to a vector and then back to a list ends up unchanged. This third function doesn’t do anything interesting on its own, but the fact that it can be compiled shows that the other two functions do what they are intended to do.

As a working programmer, the first two uses don’t excite me much. Enhanced types are cool, but they don’t come for free. I mentioned “a head function that will raise a compiler error when used on a list not known to be nonempty”. To use this function, you have to prove to the compiler that your list is nonempty, and that is not a trivial task. If you go into that without knowing what you’re doing, you will never get your program to compile. And math and logic are great, but when was the last time you had to prove statements of number theory for your day job?

In contrast, I found the idea of program verification eye-opening. If you want someone to implement some function in Python, how can you do it? Probably you write a specification in natural language, and say “That’s what I want.” But how do you know that the implementation does what the specification says? You can develop a test suite, but then you’re faced with two problems: 1) the tests only cover certain cases, and 2) how do you know that the tests cover all and only what’s in the specification? But imagine you could hand someone a function signature plus a set of signatures specifying properties of that function. To a great extent (though still not entirely), you could dispose of natural language specs and test suites, letting the compiler verify everything for you. Maybe, someday, far in the future, “If it compiles, it works!” will actually be true, and not just bluster.

By the way, I should mention that dependent types are not introduced in the book until the sixth chapter (“Precisely How Many?”), and the first third or so of the book deals only with basic generic types. That material won’t be new to everyone, but it was new to me, and it directly inspired the code changes described in “Lispier Rust with Generics”. According to my order history, the first PR to implement those changes came about two weeks after I got the book, so even at that point it would be fair to say that I got my money’s worth.

But that’s enough from me. As I said before, I asked my cat to review the book. Kemal is a domestic shorthair tabby and a self-described “run-and-gun coder” who likes to “get things done”. Here is his verbatim, unedited review:

The “Little” Typer…yeah right! This book is over 400 pages long, twice as long as the little schemer, there’s nothing “little” about it! Meow! And all so that I can beg and plead with the compiler to pretty please let me run my program! It takes me seconds to get a Python program running, do you kknow how long it takes me to get a working Idris program? Me neither, I’ll let you know whhen it finally happens. I sleep 16 hrs per day I don’t need to be bored for ther emaining 8!

Just look at the cover of the Little Schemer, it’s an elephant haviing fun, playing with toys. Now look at th e cover of the Little Typer. It’s a bunch of elephants sitting around doing paperwork! What a “purrfect” visual metaphor for dependent types!

And speaking of animals, when are these Little Schemer books going to get a cat mascot?? Theyve had elephants, bears, camels, owls, even !@#$ing cups of coffee! HSSSSSS! 5

I must confess that I sympathize with Kemal’s point of view. I even shared it until I read through the book a second time, which is when things really clicked for me. The problem is that the Little Schemer books are built around “show, don’t tell”. This works great when the benefits of something are obvious. The Reasoned Schemer, for example, shows the basic of Prolog-style logic programming. It’s not easy to figure out how it works, but it’s easy to see what it’s for – you can run functions backwards! With dependent types, it can be hard to see the forest for the trees when working with small programs.

Further Reading

- Interview with the authors (audio)

- “Propositional Logic Theorems as Types in Idris”

- “A Correctness Proof for a Simple Compiler in Idris”

Code

The code in The Little Typer is written in language called Pie that was created for the book. I don’t know if the code is online anywhere, but I rewrote most of it in Idris and put it into the Idris contrib library.

Footnotes

1 According to the incompleteness theorems, it’s not possible for a compiler to verify all good programs without also verifying some bad ones. Soundness is a virtue in this realm, so a compiler for a dependently-typed language will sometimes refuse to compile a good program.

2 There is a lot of overlap between the three areas, of course.

3 What’s the right way to refer to types that are not dependent? “Independent”? “Non-dependent”?

4 It doesn’t show how to prove that no number is both even and odd; that takes a bit more work.

5 This is technically true, but it’s worth pointing out that the illustrator for the Little Schemer books, Duane Bibby, also did the illustrations for Donald Knuth’s TeX and Metafont books, and the mascots there are lions. Bibby says:

Various animals came to mind and pad, but a classic lion finally began to pop to life. A possible source of the lion idea was a very large Maine Coon cat — a rather large breed of house cat — that was wandering around. It had been abandoned, was looking for a new home, and was giving us new arrivals the look over, trying to decide if he would adopt us. He later did. We still have cats around; [here are] Jeanette’s current guys, Cisco and Swank.