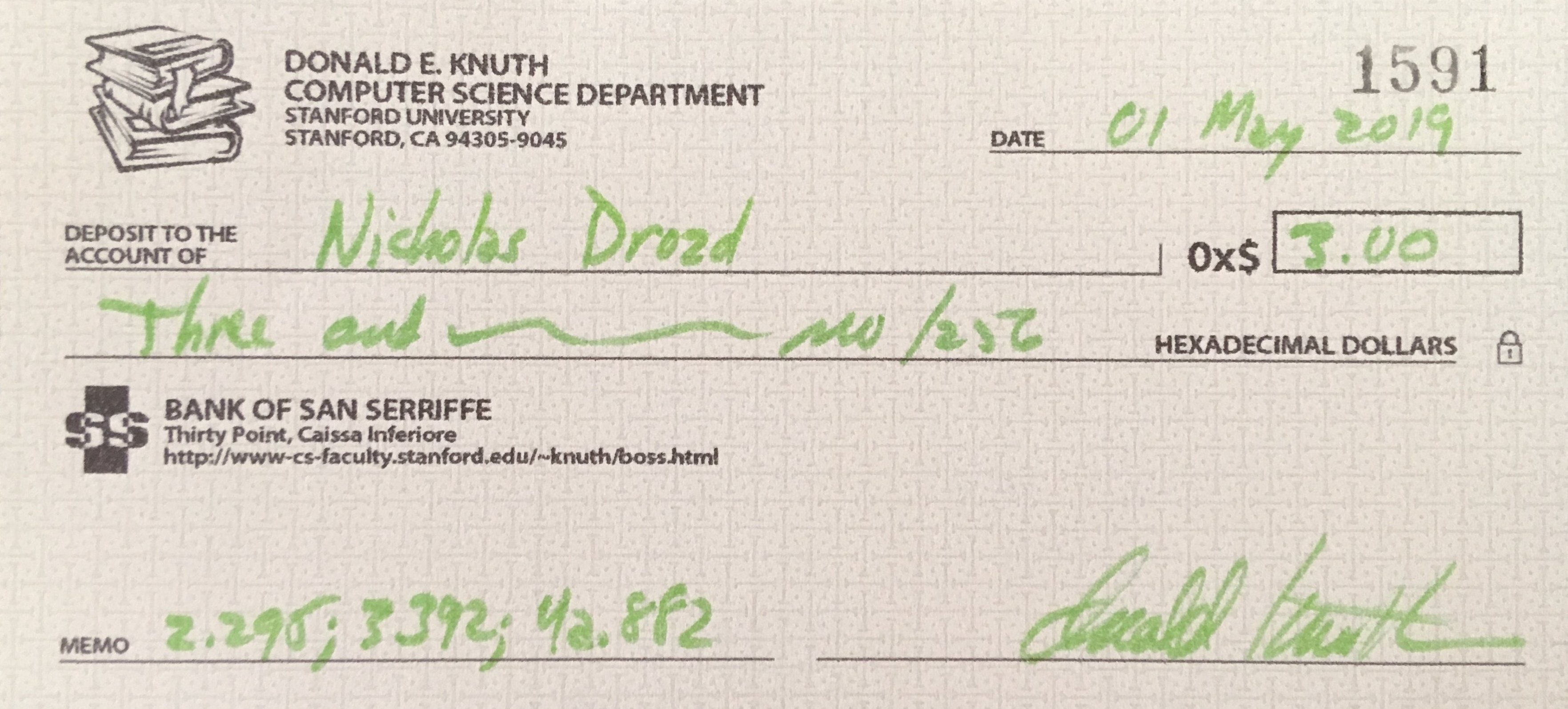

I Got a Knuth Check for 0x$3.00

Donald Knuth is a computer scientist who is so committed to the correctness of his books that he offers one US hexadecimal dollar ($2.56, 0x$1.00) for any “bug” found in his books, where a bug is anything that is “technically, historically, typographically, or politically incorrect”. I wanted to get a Knuth check for myself, so I set out to find some errors in his magnum opus, The Art of Computer Programming (TAOCP). I found three and sent them in, and true to his word, he sent me back a check for 0x$3.00.

As you can see, it’s not a real check. Knuth used to send out real checks, but stopped in 2008 due to rampant fraud. Now he sends out “personal certificates of deposit” to the Bank of San Serriffe (BoSS). He says he’ll still send real money if it’s desired, but that seems like a lot of hassle.

There are two typographical errors and one historical error. I’ll describe them in order of triviality from greatest to least.

Typo #1

The first typo is on page 392 of Volume 3, Sorting and Searching, eighth line from the bottom: “After an unsuccessful search it is sometime desirable to enter a new record, containing K, into the table; a method that does this is called a search-and-insertion algorithm.” The error is that sometime should be sometimes.

Of course, it’s no surprise that such an error should get made. This post alone is sure to contain several typos (no rewards for finding them though). What’s surprising is that it went undiscovered for so long. Page 392 isn’t buried deep in a math-heavy section, it’s the very first page of Chapter 6, “Searching”! You’d think that would be one of the most-read sections of the whole thing, and therefore also one of the most typo-free, but I guess not.

By the way, if you’ve ever thought about reading TAOCP, give it a try. A lot of people will tell you that it’s a reference work, and it’s not meant to be read straight through, but that isn’t true. The author has a clear point of view and a narrative and an idiosyncratic style, and the only thing that inhibits readability is the difficulty of the math. There’s an easy solution to that though: read until you get to math you don’t understand, then skip it and find the next section you can understand. Reading this way, I skip at least 80% of the book, but the remaining 20% is great!

People also say that TAOCP is irrelevant or outdated or otherwise inapplicable to “real programming”. This also wrong. For instance, the first section after the chapter intro deals with the basic problem of searching for an item in an unsorted array. The simplest algorithm should be familiar to all programmers. Start your pointer at the head of the array, then do the following in a loop:

- Check if the current item is the desired one. If it is, return success; otherwise

- Check if the pointer is past the array bound. If it is, return failure; otherwise

- Increment the pointer and continue.

Now consider: how many bound checks does this algorithm require on average? In the worst case, when the array doesn’t contain the item, one bound check will be required for each item in the list, and on average it will be something like N/2. A more clever search algorithm can do it with just one bound check in all cases. Tack the desired item on to the end of the array, then start your pointer at the head of the array and do the following in a loop:

- Check if the current item is the desired one. If it is, return success if the pointer is within the array bound and return failure if it isn’t; otherwise

- Increment the pointer and continue.

With this algorithm, things are arranged such that the item is guaranteed to be found one way or another, and the bound check only needs to be executed once when the item is found. This is a deep idea, but it’s also simple enough even for a beginning programmer to understand. I guess I can’t speak about the relevance for the work of others, but I was immediately able to apply this wisdom in both personal and professional code. TAOCP is full of gems like this.1

Searching, searching

For so long

Searching, searching

I just wanted to dance– Luther Vandross, Searching (1980)

Typo #2

The second typo is in Volume 4A, Combinatorial Algorithms, Part 1. There is a problem on page 60 that deals with scheduling comedians to perform at various casinos. Several real-life comedians are used as an example, including Lily Tomlin, Weird Al Yankovic, and Robin Williams, who was not dead when the volume was published. Knuth always includes full names in the indexes to his books,2 so Williams appears on page 882 as “Williams, Robin McLaurim”. But his middle name ends with an n, not an m, so it should be McLaurin.

McLaurin was his mother’s maiden name. She was the great-granddaughter of Anselm Joseph McLaurin, the 34th governor of Mississippi. His administration does not seem to have been noteworthy. According to Mississippi: A History:

The most important event of McLaurin’s administration was the United States’ declaration of war against Spain in the spring of 1898…Unfortunately the war may have given some state officials the opportunity to practice graft. McLaurin was accused of various questionable practices, including nepotism and excessive use of his pardoning powers. And in this era of mounting support for the temperance movement, the governor’s critics charged him with drunkenness, an allegation he publicly admitted.

Historical Error

Consider the traditional multiplication algorithm taught to schoolchildren. How many single-digit multiplication operations does it require? Say you’re multiplying m-digit x by n-digit y. First you multiply the first digit of x by each digit of y in turn. Then you multiply the second digit of x by each digit of y in turn, and so on until you’ve gone through each digit of x. Thus traditional multiplication requires mn primitive multiplications. In particular, multiplying two numbers each with n digits requires n2 single-digit multiplications.

That’s bad, but it’s possible to do better with a method devised by the Soviet mathematician Anatoly Alexeevich Karatsuba. Say x and y are two-digit decimal numbers; that is, there are numbers a, b, c, d such that x = (ab)10 and y = (cd)10.3 Then x = 10a + b, y = 10c + d, and xy = (10a + b)(10c + d). FOILing that out gives xy = 100ac + 10ad + 10bc + bd. At this point we still have the expected n2 = 4 single-digit multiplications: ac, ad, bc, bd. Now add and subtract 10ac + 10bd. Some clever rearranging, which I’ll leave as an exercise for the reader, yields xy = 110ac + 11bd + 10(a - b)(d - c) – just three single-digit multiplications! (There are some constant coefficients, but those can be calculated by doing only addition and bit-shifting.)

Don’t ask me to prove it, but the Karatsuba algorithm (recursively generalized from the example above) improves the traditional method’s O(n2) multiplications to O(n(lg 3)). Note that this is an actual algorithmic improvement, not a “mental math” trick. Indeed, the algorithm is not suitable for use inside the human brain, as it requires a large overhead to deal with recursive bookkeeping. Besides, the speedup doesn’t start to kick in until the numbers get fairly large anyway.4

This algorithm is described on page 295 of Volume 2, Seminumerical Algorithms. There, Knuth says, “Curiously, this idea does not seem to have been discovered before 1962,” which is when the paper describing the Karatsuba algorithm was published. But! In 1995 Karatsuba published a paper titled “The Complexity of Computations” in which he says a few things: 1) Around 1956, Kolmogorov conjectured that multiplication could not be done with less than O(n2) multiplication steps. 2) In 1960, Karatsuba attended a seminar wherein Kolmogorov pitched his n2 conjecture. 3) “Exactly within a week” Karatsuba devised his divide-and-conquer algorithm. 4) In 1962, Kolmogorov wrote and published a paper in Karatsuba’s name describing the algorithm. “I learned about the article only when I was given its reprints.”

Thus the error is that 1962 should be 1960. That’s it.

Analysis

Finding these errors didn’t take a lot of skill.

- The first typo took no skill at all to find. The error was as mundane as could be, and it was in a relatively visible place (the beginning of a chapter). Any idiot could have found it; I just happened to be the idiot who did.

- Finding the second typo required luck and diligence, but no skill. The index entry for “Williams” appears on the penultimate page of the volume, a highly visible piece of book real estate. I happened to be thumbing through the index5, and it happened to catch my eye. Because I habitually look things up on Wikipedia, I looked up Robin Williams, and I happened to notice the discrepancy.

- I wish I could say I did some serious digging to find the historical error, but really all I did was look at the Wikipedia page on the Karatsuba algorithm, the first two lines of which read: “The Karatsuba algorithm is a fast multiplication algorithm. It was discovered by Anatoly Karatsuba in 1960 and published in 1962.” After that it was just a matter of connecting the dots.

In the future, I’d like to find a more substantial bug, especially one in Knuth’s code. I’d also like to find a bug in Volume 1, Fundamental Algorithms. I might have already, but my local public library for whatever reason only has Volumes 2, 3, and 4A.

Financial facts:

-

In total, my contributions to TAOCP consist of just three characters: one added s, an n to replace an m, and a 0 to replace a 2. At $2.56 a pop, those are some lucrative characters; if you were paid $2.56/character to write 1000 words with an average of 4 characters/word, you’d clear ten grand.

-

My three hex dollars put me in a 29-way tie for being the 69th richest person in all of San Serriffe.6

Other Discussions of Knuth Checks

-

General advice for finding errors in Knuth books. It mostly applies to technical errors, which mine are not. It does have one suggestion that I took seriously:

It is better to wait until you have a collection of errors to send in. Bundling several legitimate but low-grade errors together can increase the chance that one is actually treated as an error or a suggestion. Sending several errors in piecemeal could cause each of them to be dismissed out of hand.

I didn’t want to just send in some chickenshit typos by themselves, so as per the suggestion I waited until I had the historical error, which seemed serious enough, and then sent everything in at once.

-

Ashutosh Mehra is the third-richest person in San Serriffe, with a whopping 0x$207.f0 in BoSS.

Update

The day after I posted this article, somebody submitted it to Hacker News, where it received 140 comments. And many of them were good!

Perhaps most importantly, one commenter claimed that the sometime typo was not present in the first edition of Volume 3. I went to the library to look it up myself, and it’s true: the typo was introduced in the second edition. This is good news for pedants and scavengers like me; it suggests that new bugs might always arise, and the number of bugs will never reach zero.

My description of the faster search algorithm received quite a bit of scrutiny. Many were confused by the phrase “tack the desired item on to the end of the array” – what kind of memory operation is that exactly? Others missed that part of the algorithm entirely, and assumed the algorithm was to search past the array bounds and assume that the desired key is bound to turn up sooner or later. The latter confusion might have been solved with clearer exposition, but the former seems to miss the point. After all, the algorithm is abstract, and how it gets implemented in a real programming language is a separate issue.

There was also a lively discussion about whether the algorithm provides any speedup at all in light of modern architecture and compilers. Much of it is over my head, and it’s worth reading. The consensus seems to be that sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t.

By the way, Knuth mentions a variation of that algorithm in the third chapter of his Selected Papers on Computer Science (“Algorithms”, 1977). There the algorithm iterates backwards through the list after prepending the item to the beginning. Just imagine what a shitshow it would have been if I had used that version!

The article was also posted to Reddit, where the discussion was much worse.

Finally, as predicted, there were indeed at least two bugs in this post. The first was pointed out by many commenters: techinical for technical. The second was pointed out by just one: a typo in the algebra in the Karatsuba multiplication section.

Footnotes

1 To be clear, there’s also a lot of weird stuff, like the bubble sort machine.

2 From Help Wanted:

I try to make the indexes to my books as complete as possible, or at least to give the illusion of completeness. Therefore I have adopted a policy of listing full names of everyone who is cited. For example, the index to Volume 1 of The Art of Computer Programming says ``Hoare, Charles Antony Richard’’ and ``Jordan, Marie Ennemond Camille’’ instead of just ``Hoare, C. A. R.’’ and ``Jordan, Camille.’’

3 Generalizing this algorithm to longer digits requires some bookkeeping, but isn’t too complicated. Still, I would certainly screw up the details, so I’m playing it safe by sticking with an easy example.

4 Fortunately, the Karatsuba algorithm has been superseded by even faster methods. In March 2019, an algorithm was published requiring n log n multiplications. The speedup from this method only applies to numbers that are unimaginably large.

5 This is less pathetic than it sounds, as Knuth’s indexes have Easter eggs hidden in them. For instance, the index for The TeXBook has entries for Arabic and Hebrew, and they both point to page 66. But that page doesn’t mention either language; instead, it mentions “languages that read from right to left”.

6 As of 1 May 2019.

curl https://www-cs-faculty.stanford.edu/~knuth/boss.html | awk '/0x\$[0-9a-f]+\.[0-9a-f]+/ { gsub("<[^>]*>", " "); print $NF }' | uniq -c | cat -n